The Evolution of the Brain

Or, everything you know about the brain is wrong

👋 Hey there! My name is Abhishek. Welcome to a new edition of The Sunday Wisdom! This is the best way to learn new things with the least amount of effort.

The Sunday Wisdom is a collection of weekly essays on a variety of topics, such as psychology, health, science, philosophy, economics, business, and more — all varied enough to turn you into a polymath. 🧠

The latest two editions are always free, the rest are available to paid subscribers. Now… time for the mandatory plug!

But seriously, if you are facing trouble completing the subscription above, you can alternatively make a pledge on Patreon (if you are sooo keen). Pledge whatever you are comfortable with and I’ll unlock paid posts for you — all 200+ of them. Deal?

Alright! On to this week’s essay.

What if I told you that everything you thought you knew about the brain is wrong? The brain has long been considered to have three components — the reptilian brain, the limbic system, and the neocortex. What if I told you it’s not exactly true? What if I told you that your brain blueprint is very similar to that of an iguana?

They key idea is borrowed from Lisa Feldman Barrett’s Seven and a Half Lessons About the Brain. It’s about 1,400 words.

Q: Do human beings really have a reptilian brain?

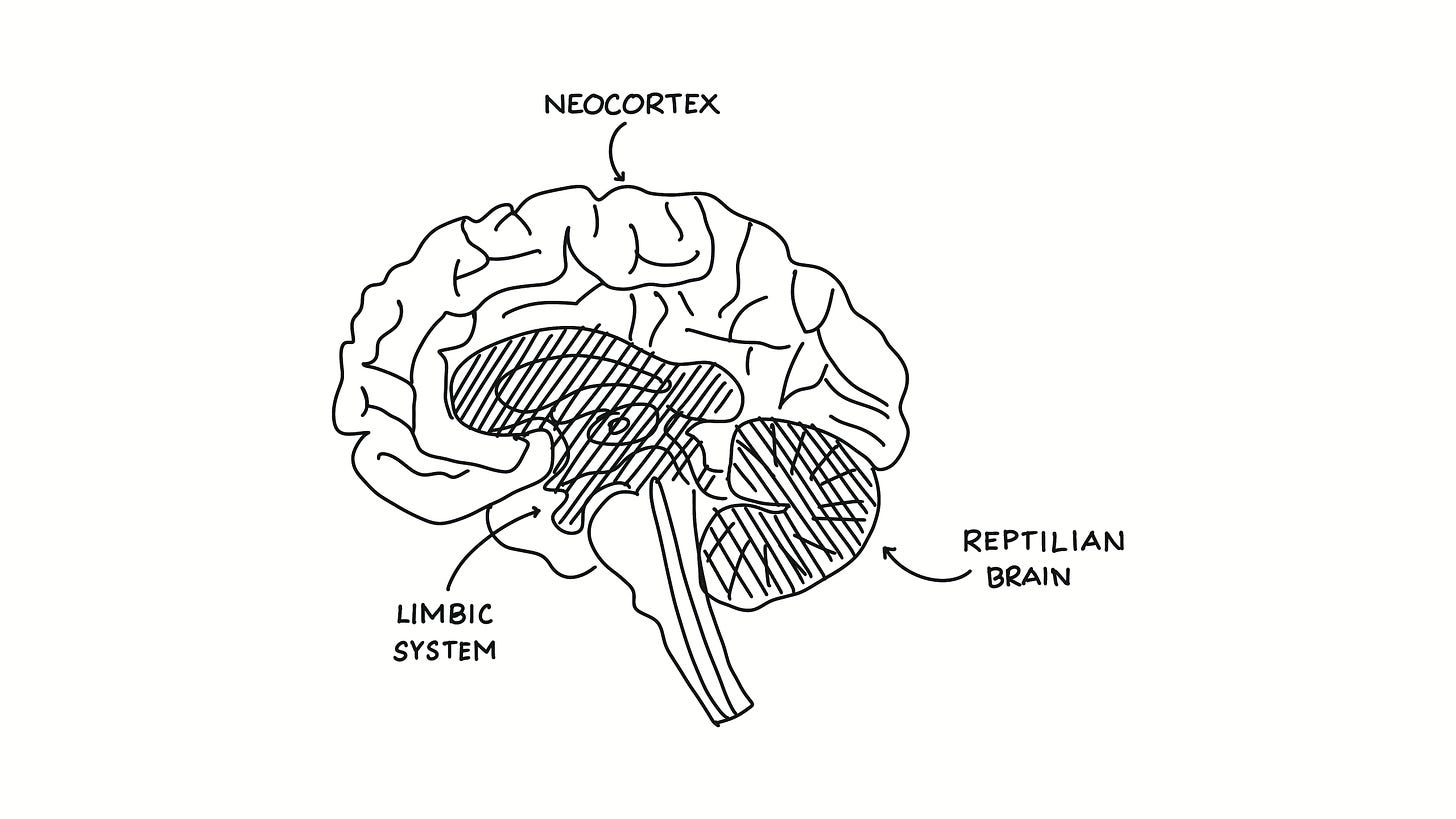

The human brain can be divided into three distinct evolutionary components, each responsible for different functions.

First up, we have the Reptilian Brain, or as scientists like to call it, the “R-Complex.” This old-school brain is the primitive part that reptiles also have. It’s in charge of basic survival instincts and behaviours. Think of it like the bouncer of your brain, regulating things like breathing, heart rate, and getting all territorial and aggressive when necessary.

Next, we have the Limbic System, aka the “Paleomammalian Brain.” This one is the emotional and social centre of your brain and is all about feelings and memories. It’s like the emotional DJ, spinning tunes of joy, fear, and motivation. Plus, it keeps an eye on your body’s responses to different situations.

Lastly, we have the Neocortex, aka the “Neomammalian Brain.” This is the superstar of the brain, especially in us humans. It’s responsible for all the fancy thinking, language, and problem-solving skills. Basically, it’s the brain’s genius scientist, coming up with brilliant ideas and making decisions like a boss.

This arrangement, as was proposed by by neuroscientist Paul D. MacLean in the 1960s is known as the triune brain. Carl Sagan introduced this to the wider public in his 1977 book The Dragons of Eden, which won a Pulitzer Prize.

One part of the neocortex, called the prefrontal cortex, regulates our emotional brain and our reptilian brain to keep our irrational, animalistic self in check. Humans have a very large cerebral cortex, which is an evidence of our distinctly rational nature.

But there’s a slight problem. The triune brain idea is complete bogus!

We don’t really have brain parts that are dedicated to surviving, feeling, and thinking. The triune brain idea is one of the most successful and widespread errors in all of science. It’s nothing but an oversimplified version of an extremely complex and nuanced system.

The triune brain idea is a compelling story and it kind of captures how we feel in daily life. For example, when you see that cheese cake and your taste buds start tingling, it feels as if your impulsive inner reptilian brain and emotional limbic system are urging you to indulge in a cakey adventure.

But then your rational neocortex jumps into action with a sensible advice: “Hold on a second! You just had breakfast.” Your neocortex engages in a mental wrestling match with the inner lizard and emotional limbic system, trying to bring them under control.

But human brains don’t work that way. Bad behaviour doesn’t come from ancient and unbridled inner beasts. Good behaviour is not the result of rationality. And rationality and emotion are not at war. They do not even live in separate parts of the brain.

Now, MacLean wasn’t stupid. And back then he didn’t have fancy technology like we do now. He relied on a good ol’ microscope and his sharp eyes to build and prove his hypothesis.

When he peered through that microscope, examining the brains of lizards, mammals (including humans), and other creatures, he noticed something interesting. Humans had some parts that other mammals didn’t, which he called the neocortex. And mammals had other parts that reptiles didn’t, which he named the limbic system. With these discoveries, MacLean created a captivating story about the origins of humanity.

MacLean’s ideas were simple yet elegant, and they aligned with Charles Darwin’s thoughts on human evolution in The Descent of Man. Darwin believed that as our bodies evolved, so did our minds. According to Darwin, each of us carries an ancient inner beast that we tame through rational thinking.

But today’s neuroscientists have even more tools at their disposal than just sharp eyes. By comparing the genes in different species, they can trace our shared ancestry and understand how our brains have evolved over time.

Interestingly, they have found that even though neurons may look different in different species, they can still contain the same genes. This suggests that these neurons share a common origin. So, if certain genes are present in both human and rat neurons, it’s likely that our last common ancestor had similar neurons.

But here’s the thing: Evolution doesn’t work like adding layers to a cake or stacking rocks. It’s not about piling up new brain parts over time. If that were the case, human and rat brains would look very similar. So… the question is: How exactly did our brains come to differ if not by adding layers?

Brains change and reorganise as they evolve and grow larger over time. Let me illustrate. Your brain has four groups of neurons, or brain regions, responsible for sensing body movements and creating your sense of touch. Together, they’re called the Primary Somatosensory Cortex.

Now, in a rat’s brain, things are a bit different. Rats have just one region that does similar tasks, known as the primary somatosensory cortex. If we were to judge by looks alone, like MacLean did, we might mistakenly believe that rats lack the three somatosensory regions found in the human brain. We might think that these three regions are newly evolved in humans and have unique functions just for us.

But here’s the fun part: your four regions and the rat’s single region share many of the same genes. This tells us something important about evolution. It suggests that around 66 million years ago, our last common ancestor with rodents probably had a single somatosensory region that performed some of the functions carried out by our four regions today.

As our ancestors’ brains and bodies evolved to become larger and more complex, that single region most likely expanded and divided into multiple regions, redistributing its responsibilities. This whole process of segregating and then integrating brain regions creates a more intricate brain capable of controlling a larger and more intricate body.

Recent discoveries in molecular genetics have found that reptiles, nonhuman mammals, and humans have similar types of neurons, including the ones responsible for the famous neocortex. So, forget the idea that human brains came from reptiles by adding extra parts for emotion and rationality. Something way more interesting happened!

Neuroscientists have found that all mammals, and possibly even reptiles and other vertebrates, follow a single blueprint during brain development. It’s fascinating because this blueprint unfolds in a very predictable way, starting shortly after conception when neurons begin to form.

The order in which neurons are created remains the same across various mammalian species, from tiny mice and rats to adorable dogs, cats, horses, and yes, us humans. And there’s strong evidence suggesting that this order applies to reptiles, birds, and some fish too. So, scientifically speaking, you and a hagfish have the same brain blueprint.

But here’s the hilarious part. If all these vertebrates follow the same developmental order, why do their brains look so different? It’s all about timing!

See, the manufacturing process of the brain runs in stages, but the duration of each stage varies among species. The building blocks are the same, but it’s like a game of “Wait, wait, not yet” in different timeframes.

For example, the stage responsible for creating neurons for the cerebral cortex in humans runs for a shorter time in rodents and even shorter in lizards. That’s why your cerebral cortex is big, a mouse’s is smaller, and an iguana’s is tiny, almost nonexistent.

So, the bottom line is this: The human brain doesn’t have any fancy new parts. The neurons in your brain can be found in the brains of other mammals and probably other vertebrates too. This discovery messes with the whole evolutionary story of the triune brain.

Now, imagine if we could perform some magical intervention and make that stage in a lizard last as long as it does in humans. Voila! We’d get something similar to a human cerebral cortex. But here’s the catch: it wouldn’t function like a human one. Size isn’t everything, even for a brain.

Today I Learned

Esperanto is an artificial language created by Polish ophthalmologist and linguist L.L. Zamenhof in the late 19th century.

It has a flexible and logical grammar system, making it relatively easy to learn compared to natural languages. Its vocabulary is primarily based on roots from European languages, allowing speakers of different linguistic backgrounds to recognise and understand words easily.

Zamenhof developed Esperanto with the goal of fostering international communication and understanding among people of different linguistic backgrounds.

Born in 1859 in Białystok, Poland, when was then part of the Russian Empire, and growing up in a multi-ethnic and multilingual community, Zamenhof witnessed the communication barriers and conflicts that arose due to language differences. Inspired by the idea of a universal language, Zamenhof began developing Esperanto in the 1870s while still a student.

Zamenhof published the first book detailing Esperanto, “Unua Libro” (First Book), in 1887 under the pseudonym “Doktoro Esperanto,” which means “Doctor Hopeful.” The word “Esperanto” itself derives from this pseudonym and translates to “one who hopes.”

Zamenhof believed that by fostering communication and understanding, Esperanto could contribute to peace and harmony among nations. It is designed to be politically and culturally neutral, devoid of any national or ethnic associations.

Now, technical and scientific languages are really good at being precise and effective within their specific fields. But language itself goes beyond those limited uses. Language is like a versatile tool that can be shaped to serve many different purposes because it can adapt and change.

The long history of a language that’s been passed down through generations gives it a lot of meanings and connections, which keeps it flexible.

Creating an artificial language is kind of like trying to design a city from scratch. Just like a pre-planned city, it doesn’t respect the unique goals and perspectives of the people who live there. Just like an artificial language, It also doesn’t leave enough room for the unexpected ways that people interact with it and the outcomes that come from that.

Having said that, despite its shortcomings, Esperanto represents an intriguing experiment and stands as a testament to the human desire for a universal language that transcends cultural and linguistic barriers.

Interesting Finds

Psychophysics is a discipline invented by Gustav Fechner in the 19th century. Psychophysics sought to establish a measurable connection between the physical world and human perception, using mathematical and statistical techniques. Fechner’s ideas influenced the development of experimental psychology and the creation of sensing machines to measure and quantify sensory experiences. Today, psychophysics continues to be relevant in fields like virtual reality and augmented reality, where researchers use sensors, statistical modelling, and computing power to capture and simulate human perception.

In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, Bertrand Russell delves into the complex motivations driving human behaviour. He challenges the notion that desire can be resisted in the pursuit of duty and moral principle, emphasising that desire is the central force behind all human activity. Russell explores four infinite desires — acquisitiveness, rivalry, vanity, and love of power — and their profound influence on our lives. He examines how these desires intertwine and shape our actions, highlighting their insatiable nature and their impact on individuals and society as a whole. Russell also considers secondary motives such as the love of excitement and the need for constructive outlets to channel our innate impulses.

The public bench is a fascinating thing. It’s symbol of urban life and the city’s capacity for welcome and generosity. It represents both deliberate isolation and a presence in the public arena. Whether it’s a solitary moment of idling or a social space for conversation, the bench captures the range of human emotions and experiences. Photographers have been drawn to the bench, capturing scenes that reflect the city’s diversity. From intimate embraces to isolated figures, these images convey the complex relationship between individuals and the urban environment. The bench also serves as a refuge, a haven for the tired and homeless, offering a respite from the ground. It embodies both comfort and hardship, making it a versatile and poignant element of the urban landscape.

Timeless Insight

Big breakthroughs typically follow a seven-step path:

First, no one’s heard of you or your idea

Then they’ve heard of you, but think you’re nuts

Then they understand your idea, but think it has no opportunity

Then they view your idea as a toy

Then they see it as an amazing toy

Then they start using it

Then they couldn’t imagine life without it

This process can take decades. It rarely takes less than several years.

What I’m Reading

The consequences of women’s attractiveness for a man’s social status are critical. Everyday folklore tells us that our mate is a reflection of ourselves. Men are particularly concerned about status, reputation, and hierarchies because elevated rank has always been an important means of acquiring the resources that make men attractive to women. It is reasonable, therefore, to expect that a man will be concerned about the effect that his mate has on his social status

— David M. Buss, The Evolution of Desire

Tiny Thought

You should obsess over risks that do permanent damage and care little about risks that do temporary harm, but the opposite is more common.

Before You Go…

If you’re finding this newsletter valuable, share it with a friend, and consider subscribing. If you aren’t ready to become a paid subscriber yet, but feel like I’ve done a good enough job writing today’s issue, you can also support me by buying me a cup of coffee. ☕️

I’ll see you next Sunday,

Abhishek 👋

PS: All typos are intentional and I take no responsibility whatsoever! 😬