Don’t Pursue Dramatic Changes

Or, how to make time work for you

Welcome to Issue 59!

Here’s a thought.

Others are already paying attention to your weaknesses. So you better spend time identifying your strengths and honing your skills. If your weaknesses are crucial, delegate them.

If writing is your strength, but the technical knowhow required to setup a blog isn’t your forte, delegate it. Hire a developer or use a publishing platform. As long as your strengths alone can give you strategic advantage, you should delegate your weaknesses.

— Abhishek

When we plan to improve ourselves, we pursue dramatic changes, committing to goals like, “Running 10 km starting tomorrow” when we haven’t even been taking daily strolls. Or, “Waking up at 6 everyday” when we’ve been sleeping till 9 all our life. This approach is unsustainable. If you don’t believe me, make a list of the promises you’ve made yourself over the years, and see how many of them you’ve kept.

A better approach is to go for small, with incremental improvements that add up over time—results that compound.

Investor Morgan Housel is one of the best thinkers of our times. He tells the following story to explain how compounding works. It’s about how ice age happened.

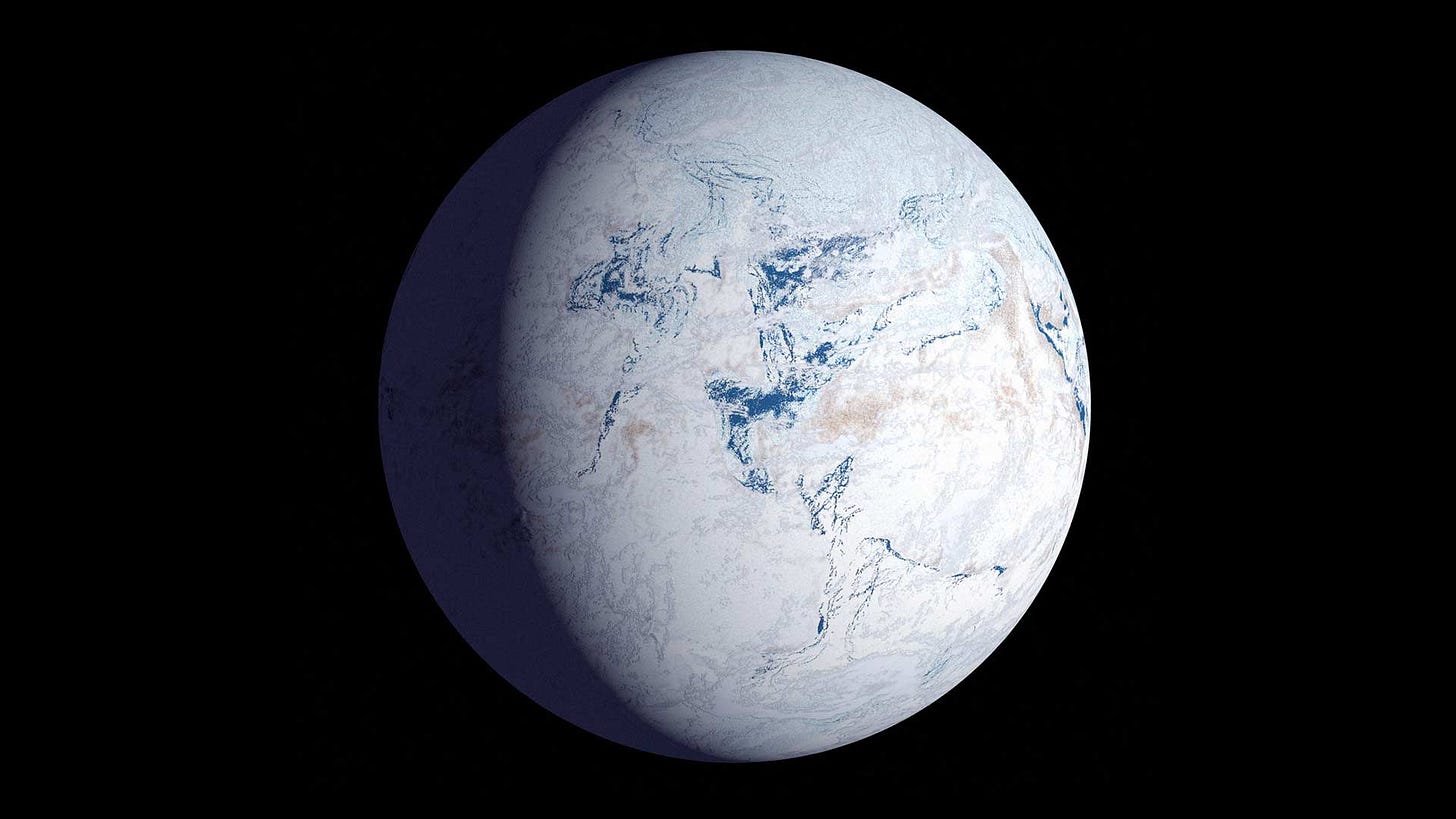

There have been at least 5 major ice ages in the earth’s history. The whole earth was covered in 3–4 km thick ice sheets. If you were to answer how this happened, you would most likely say long and cold winters led to that. That’s incorrect. As unintuitive as it sounds, instead of cold winters, it was moderately cool summers that led to ice age.

It starts when one fine summer it didn’t get warm enough to melt away previous winter’s snow. The leftover snow makes it easier for more snow to accumulate in the next summer which is relatively cooler as well. Now we’ve got all these leftover snow which attracts even more snow that accumulate the following winter. Give it a few hundred years, and a seasonal snowpack grows into a continental ice sheet, and the whole earth gets covered in snow.

The same happens in reverse. An orbital tilt lets more sunlight in, which increases temperature, melts more snow one fine summer, which prevents more gathering of snow the next year, and so on.

You start with one cool summer that no one would think anything of, and suddenly the earth gets covered in thick ice. It’s not about how much snow is gathered a season. It’s more about how much lasts. The takeaway is that you don’t need big forces like long and hard winters to create tremendous results of this scale.

Similarly, Warren Buffett is a phenomenal investor. But most people miss the point that he’s been doing serious investing since age 10. He wished he started earlier.

He has been compounding returns for 75 years. With his track record, had he started investing at 30, and retired at 60, few people would have heard of him.

Interestingly, Buffet maybe the richest investor of all time, but he’s certainly not the greatest—not when he is measured by his annual returns. There are several hedge fund managers who have compounded 2x or 3x times Buffett’s rate, but their net worth is not even close to Buffett. Because most of them haven’t been in business for more than a few decades decade. Time isn’t on their side.

Had Buffett spent his twenties travelling and soul searching; had he retired at the age of 60 to spend time with this grand kids, with 22% annual returns, he would have made about $12 million in total—which is 99.9% less than his actual net worth of $85 billion. Even though his skill is investment, Buffett’s secret is time.

Warren Buffett is the ultimate example. If you manage to have minimum returns, and not to lose money for a long time, you are bound to get rich. The trick is to make time your ally so that the longer you play the better your prospects become.

Paul Graham, the founder of Y Combinator, is fond of saying, “A startup is a company designed to grow fast.” Most founders take this at face value, and focus on growth at breakneck speed. But what PG talks about is consistent growth that compound with time, not one time flukes.

A company that grows 1% a week will grow 1.7x a year, whereas a company that grows 5% a week will grow 12.6x. But a company that grows at 10% a week will grow 142.0x a year. Tiny changes in the present compound to massive differences in future.

However, most startups fail in the first 2 years. They focus on growth at the expense of survival. But you cannot grow if you aren’t in business anymore. 10% a week might look tiny in the beginning, but it’s enough for compound interest to kick in and takeover after an initial slog. You don’t need maximum efficiency. You don’t need maximum returns. You don’t need maximum productivity. You need the bare minimum that lets you play the game long enough to have an edge in the future.

Linear growth is intuitive. If I ask you to calculate 5+5+5+5+5+5+5+5+5 in your head, you can do it in a few seconds. If I ask you to calculate 5×5×5×5×5×5×5×5×5, your head will explode. Calculating exponential growth requires a calculator. Paul Graham writes:

Our ancestors must rarely have encountered cases of exponential growth, because our intuitions are no guide here. What happens to fast growing startups tends to surprise even the founders.

Compounding does not work for the first 2–5 years, but it works for the next 20–50 years. Warren Buffett added most of this wealth after his 65th birthday. Most people don’t have that kind of patience.

The counterintuitiveness of compounding is responsible for the majority of disappointing trades, bad strategies, and successful investing attempts.

Compound Thinking is thinking in terms of compounding and exponential growth. Since it is not intuitive, majority fail to notice it—even the smartest of the lot. That’s why it gives you an unfair advantage. It’s the most powerful open secret weapon.

As Morgan Housel writes:

Good investing isn’t necessarily about earning the highest returns, because the highest returns tend to be one-off hits that can’t be repeated. It’s about earning pretty good returns that you can stick with and which can be repeated for the longest period of time. That’s when compounding runs wild.

Life Learnings

I’m a big fan of Maria Popova. After running Brain Pickings for 13 years, she listed 13 life learnings. Here are my favourites, in no particular order.

Allow yourself to change your mind. It’s good to have an opinion. It’s fatal to have a weak opinion based on superficial impressions. It’s disorienting to say, “I don’t know,” but it’s rewarding to ‘understand’ than to be ‘right’—even if that means changing your mind about a topic, an ideology, or yourself.

Never do anything for prestige alone. Prestige warps your beliefs about what you enjoy. Prestige causes you to work not on what you like, but what you’d like to like. It’s rewarding in the short run, but detrimental in the long run. Prestige distracts you from deeper rewards.

When people, whoever they are, tell you who you are, ignore them. You know more about yourself than anybody else. What they think about you reveal more about them, and nothing about you. Wittgenstein’s Ruler.

Spend your days as you would spend your life. We are measured by how much we work, how much we make, and how efficient we are. Instead we should measure our lives by the amount of joy and wonder we create that makes our lives worth living.

Play the long game. Make time your friend. Expect anything worthwhile and long-lasting to take a long time to come to fruition. Overnight success is a myth. The 250-year-old Great Banyan in West Bengal didn’t occupy ~19,000 sq. metre on the first day, or the first year, or the first 10 years. All good things take time. But if you find joy in the process, it shouldn’t matter how long it takes.

All models are maps. All maps are approximates. They may not be accurate, no matter how common or popular they are. Question your maps, models, opinions, and ideas. Continually test them against reality.

No Room to Grieve

Journalist Anne Helen Petersen talks about how it has become difficult for us to grieve in these times because of the pandemic. Grief requires human touch, which has been replaced by video calls and endless screen time. The process of grieving itself has become exhausting.

Sometimes grief requires solitude. But it also often demands fellowship—and space to linger.

These days it’s almost a privilege to feel physically safe and economically stable. For families that have suffered job losses along with the loss of loved ones, there is a real and existential fear apart from grief.

All these systems that are supposed to protect us from this sort of grief, or at the very least ease it, are broken as shit—and have been for some time. That brokenness has created new inequities, but it’s also exacerbated old ones. The grief is not evenly distributed now, and it was not evenly distributed before.

Although she talks about the US, the sentiment applies to India and several other countries. When there’s scarcity of food (among families who depend on daily wages), grieving for the loss of a member becomes secondary.

It’s a privilage to have a job, food on a table, and a healthy family now—all that we take for granted.

The Future of Journalism

An NYT article talks about the new trend of journalists leaving publication houses to start paid newsletters of their own.

The news media business has been in steady decline. Roughly half of all newspaper jobs are gone, and thousands of journalists are being laid off. On top of that, people who care about journalism have lost faith in the news. News isn’t news anymore. It has become a propaganda engine.

Another possible reason, as mentioned on the Patreon Blog, is the lack of diversity in big publications. Similar stories get told from only a few perspectives that are very similar. “You don’t have the proper perspective and the proper diversity in these institutions to tell the stories that need to be told on the ground,” says reporter Oumar Salifou.

Journalism is no longer a one-way conversation — whether it’s through social media, email newsletters. The days of only knowing a reporter through their byline are over.

The new form of journalism is built on an intimate connection between the writers and their readers. Going solo means journalists can dedicate their time and energy to the stories that matter most to themselves and their audience. As the chief executive of Substack, the newsletter publication platform on which Sunday Wisdom is hosted, Chris Best says, “It’s not about getting the most retweets. It’s about convincing people to part with their money because they trust you.”

As a culture, we rely on journalists, writers, and storytellers now more than ever. When we lack understanding, they help us make sense of the rapidly changing world we live in, and when we need a moment from it all, they help us escape until we’re ready to dive back in.

Journalists are launching solo paid publications because chasing advertisers is a pain. The upside is that going paid means living up to the expectations of the audience, not the advertisers, or a publication, or a political party. This gives them the freedom to become more authentic.

People who pay for good content don’t care about sensational entertainment. Journalists would have to write for the subject’s sake, not for writing’s sake. The quality of content can only get better from here. Demand and supply.

This doesn’t mean that the publication houses would die away. 99.9% of the people would be watching the news for free. In India, news is the most socially acceptable form of entertainment. It’s heavily encouraged by all parents. But solo newsletters would provide the 0.01% minority an avenue to read the real news.

Fantastic Abhishek! Great insights ! Would love to talk to you ! I am @GoyankaParth on Twitter

Abhishek, love this new format of the newsletter with the brief summaries and commentaries. I feel I have learnt a lot in just a couple of minutes. Keep up the good work!