Biography of Depression — Part I

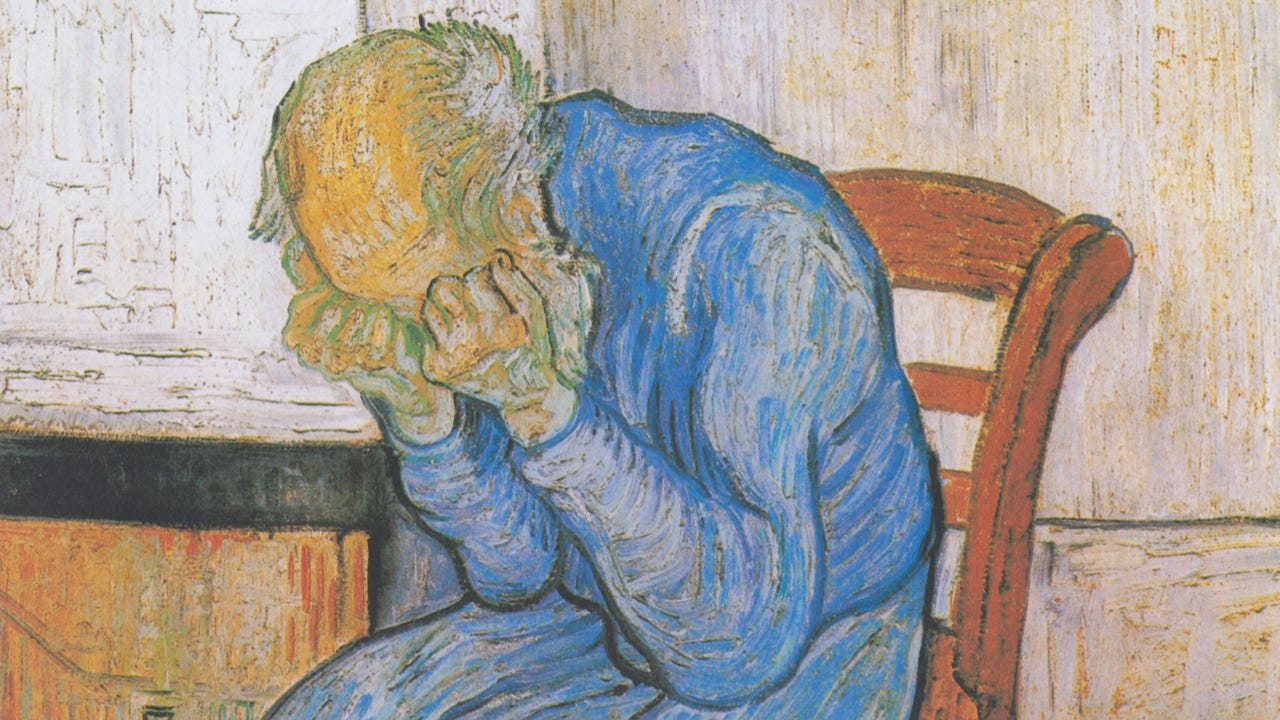

Or, how major depression is very very different from just “feeling depressed”

👋 Hey there! My name is Abhishek. Welcome to a new edition of The Sunday Wisdom! This is the best way to learn new things with the least amount of effort.

The Sunday Wisdom is a collection of weekly essays on a variety of topics, such as psychology, health, science, philosophy, economics, business, and more — all varied enough to turn you into a polymath. 🧠

The latest two editions are always free, the rest are available to paid subscribers. Now… time for the mandatory plug!

But seriously, if you are facing trouble completing the subscription above, you can alternatively make a pledge on Patreon (if you are sooo keen). Pledge $2 (or more) and I’ll unlock paid posts for you — all 150+ of them. Deal?

Alright! On to this week’s essay, which is the first part of a two-part series. The key ideas are borrowed from Robert M. Sapolsky’s Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers. It’s about 1,950 words.

Q: Is depression an actual medical disease or just a state of mind?

Depression is one of the leading causes of disability worldwide. It is characterised by persistent feelings of sadness, loss of interest or pleasure, changes in appetite or sleep patterns, low energy, and difficulty concentrating.

The best estimates from the early 2000s suggest that 5 to 20 percent of us will suffer a major, incapacitating depression at some point in our lives, causing us to be hospitalised or medicated or nonfunctional for a significant length of time.

These estimates have no doubt grown significantly in the last twenty years. Today, over 264 million people of all ages suffer from depression globally. That’s roughly 1 out of every 30 people on the planet. In comparison, Indonesia’s total population is 273 million.

Yet, a lot of us have a bad habit of treating depression as fugazi, as if it isn’t real, not to mention the vast amount of stigma attached to it.

Part of the problem is that “depression” is a term we throw around in an everyday sense. Something mildly or fairly upsetting happens to us — boss said something snarky, had a fight with romantic partner, didn’t get much sleep last night — and we get “the blues” for a while, followed by recovery. But this is not what occurs in a major depression.

One characteristic of a major depression is chronicity — the symptoms have persisted for at least two weeks. The other is severity — which in its worst form can lead people to even attempt suicide.

Depression’s victims may lose their jobs, family, and all social contact because they cannot force themselves to get out of bed, or refuse to go to a psychiatrist because they feel they don’t deserve to get better.

It’s a horrific disease, and this essay is about this devastating form of depression, rather than the transient blues that we may casually signify with the term “feeling depressed.”

The defining feature of a major depression is loss of pleasure. You stop appreciating sunsets, enjoying boardgames, and valuing the smell of freshly brewed coffee.

This trait is called anhedonia (or dysphoria): hedonism is “the pursuit of pleasure,” anhedonia is “the inability to feel pleasure.” Anhedonia is consistent among depressives.

A woman has just received the long-sought promotion; a man has just become engaged to the woman of his dreams — yet, they will tell you how they feel nothing, how it really doesn’t count, how they don’t deserve it. Friendship, achievement, sex, food, humour — none bring any pleasure.

Accompanying major depression are often great grief and obsessive guilt. We often feel grief and guilt in the everyday sadnesses that we refer to as “depression.” But in a major depression, they can be incapacitating, as the person is overwhelmed with the despair.

This guilt may not necessarily be about something that has contributed to the depression, but about the depression itself — what it has done to the sufferer’s family, the guilt of not being able to overcome depression, a life wasted amid this disease. No wonder that depression accounts for 800,000 suicides per year worldwide.

Sometimes, the sense of grief and guilt can take on the quality of a delusion — where facts are distorted and over- or under-interpreted to the point where it constantly feels that things are terrible, and only getting worse with each passing day.

For example, while recovering from some sort of ailment, you might actually be getting better — everybody says you are getting better, even your doctor is seeing good progress — but you are of the opinion that you aren’t getting any better and everybody is simply trying to be nice to you.

This is why depression is sometimes considered as a disorder of thought, rather than emotion. For example, if you show subjects two pictures for a split second (such that they can barely register what’s in them) where one picture has a group of people gathered happily around a dinner table, and another picture has the same people gathered around a coffin, which one do you think is remembered? Depressives see the funeral scene at rates higher than normal.

Depression not only kills all the joy in life, but also makes you see everything in a distorted manner that reinforces the lack of joy in everything.

As clinical psychologist Julie Smith writes: “Thoughts are not facts. They are a mix of opinions, judgements, stories, memories, theories, interpretations, and predictions about the future.” For someone suffering from depression, their glasses are perpetually half empty.

Another frequent feature of a major depression is called psychomotor retardation. Everything requires tremendous effort and concentration. They find the act of merely arranging a doctor’s appointment exhausting. Soon it is too much even to get out of bed in the morning. (It should be noted that some patients also show an opposite pattern, termed psychomotor agitation — there’s so much energy that it becomes overwhelming.)

Psychomotor retardation is one of the reasons why severely depressed people rarely attempt suicide. If the psychomotor aspects make it too much for this person to get out of bed, they sure aren’t going to find the often considerable energy needed to do something drastic. It’s not until they begin to feel a bit better that such thoughts occur.

Many of us tend to think of depressives as people who get the same everyday blahs as you and I, but it just spirals out of control for them. They are people who just can’t handle life’s ups and downs like the rest of us. That’s not the case. This is equivalent to blaming diabetics for not being able to control their blood sugar level like normal people.

Let me illustrate with an example. Suppose you are recovering after a serious physical injury. You are very likely to feel a certain absence of pleasure during the process. You might experience a lingering sense of grief as well. You’ll also have mild psychomotor retardation — you’re not as eager for your callisthenics as usual. Sleeping and feeding may be disrupted, sex may lose its appeal for a while. Hobbies may not be as enticing anymore. You don’t enjoy meeting friends just as much. This is exactly how a person suffering from depression feels like.

On an incredibly simplistic level, depression occurs when you think an abstract negative thought and your brain manages to convince you that this is as real as a physical stressor. In this view, people with chronic depressions are those whose brain habitually whispers sad thoughts to them.

Major depression is as real a disease as diabetes. Not unlike diabetes, many things in the bodies of depressives work peculiarly. These are called vegetative symptoms.

Whenever you and I feel a bit depressed in the colloquial sense, what do we do? Typically, we sleep more than usual, probably eat more than usual, convinced in some way that such comforts will make us feel better.

These traits are just the opposite of the vegetative symptoms seen in most people with major depressions. Eating declines. Sleeping does as well, and in a distinctive manner. While depressives don’t necessarily have trouble falling asleep, they have the problem of “early morning wakening,” spending months on end sleepless and exhausted from three-thirty or so each morning.

An additional vegetative symptom is elevated levels of glucocorticoids in the body. (Glucocorticoids are fascinating compounds that belong to a class of steroid hormones that are produced naturally in the adrenal glands. They play a vital role in regulating various physiological processes in the body. One of the most well-known glucocorticoids is the stress hormone called cortisol.)

When looking at a depressive person sitting on the edge of the bed, barely able to move, it is easy to think of the person as energy-less, enervated. A more accurate picture is of the depressive as a tightly coiled spool of wire, tense, straining, active — but all inside.

As Matt Haig writes in Reasons to Stay Alive: “People with mental illnesses aren't wrapped up in themselves because they are intrinsically any more selfish than other people. Of course not. They are just feeling things that can't be ignored. Things that point the arrows inward.”

This person is fighting an enormous, aggressive mental battle — no wonder they have elevated levels of stress hormones.

Elevated glucocorticoid levels in depression is cause of another feature of the disease, which is problems with memory. Memory problems are also partly due to lack of motivation (why work on some shrink’s memory test when everything, everything, is hopeless and pointless) and due to the anhedonic inability to respond to the rewards of remembering something in a task.

Nonetheless, amid those additional factors, the process of storing and retrieving memories via the hippocampus (the grand librarian gland in the brain responsible for diligently cataloguing and organising memories) is often impaired. In fact, it is found that the hippocampus is smaller than average in many chronic depressives.

Just like diabetes, depression has types, and they look quite different. In one variant, unipolar depression, the sufferer fluctuates from feeling extremely depressed to feeling reasonably normal. In another form, the person fluctuates between deep depression and wild, disorganised hyperactivity. This is called bipolar depression or manic depression. Again, manic depression is not to be confused with mania or madness in everyday sense, or be related to made-for-television homicidal maniacs. Mania found in manic depression is of a completely different magnitude.

An example of a manic-depressive would be someone who doesn’t have a cent to their name, no job, no real prospect, knee-deep in debt, but have recently bought three luxury cars with money from loan sharks. And get this, they don’t even know how to drive.

People in manic states will go for days on three hours of sleep a night and feel rested, will talk nonstop for hours at a time, will be vastly distractible, unable to concentrate amid their racing thoughts.

In outbursts of irrational grandiosity, they will behave in ways that are foolhardy or dangerous to themselves and others — at the extreme, poisoning themselves in attempting to prove their immortality, burning down their homes, giving away their life savings to strangers. It is a profoundly destructive disease.

A manic-depressive may be manic for five days, severely depressed for the following week, then mildly depressed for half a week or so, and, finally, symptom-free for a few weeks. Then the pattern starts up again, and may have been going on for a decade. Good things and bad things happen, but the same cyclic rhythm continues.

All said and done, depression, like hypertension, is also genetic. The more genes two people have in common, the more likely they are to share a depressive trait. Now, it doesn’t mean that if you have “the gene“ you’re a gone case. It simply means that all things being equal, your chances of getting depression is relatively high.

But… like heart disease, cancer, and high blood pressure, there’s an umpteen number of factors that decide if you would contract depression or not. As long as you take care of them, you are good. In fact, if you share every single gene with someone who is depressive, you still have a 50 percent chance of not having the disease. Probability after all is not destiny.

Today I Learned

Here’s a historical anecdote about amphetamines.

Amphetamines are a class of psychoactive drugs that stimulate the central nervous system. They belong to the larger group of stimulant drugs and are known for their effects on increasing alertness, attention, and energy levels.

Amphetamines work by increasing the levels of certain chemicals in the brain, such as dopamine and norepinephrine, which play a role in regulating mood, motivation, and cognitive functions.

Adderall, the prescription medication often prescribed for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and narcolepsy is an amphetamine.

But that’s not the point. Did you know that in the early 1960s, doctors prescribed large amounts of dopamine-boosting amphetamine to promote “cheerfulness, mental alertness, and optimism,” (as described by a contemporary advertisement)?

Most of these prescriptions were written for women, who were twice as likely as men to be prescribed amphetamine to “adjust their mental state.” As one doctor described it, amphetamine allowed them to be “not only capable of performing their duties, but to actually enjoy them.” In other words, if you don’t like cooking or cleaning, it helps to be on speed.

But that’s not all. In addition to making housewives happy and productive, it also kept them thin. According to Life magazine, two billion tablets were prescribed annually in the 1960s for this purpose alone. But although people did lose weight, it was only temporary, and often at a high cost.

Stop using the drug, and the weight comes right back. Keep using the drug and tolerance develops, so the user must take higher and higher doses to get the same effect. That’s dangerous. Too much amphetamine can bring about personality changes. It can also cause psychosis, heart attacks, strokes, and death.

“I felt charming, witty, and clever, talking to everybody,” wrote one amphetamine user. “I felt a compulsion to make subtle, condescending comments to the more-dimwitted customers [at work] under the guise of being straightforward and helpful. My family has also told me that I’ve become much more arrogant, snide, and condescending, and my brother tells me that I’ve been thinking I’m ‘hot shit’ lately, but he might be jealous of me.”

Another user said simply, “I used to feel like a young god on speed.” The difference is that young gods don’t suffer side effects that kill.

Timeless Insight

People naturally lose focus when they forget that focus means saying no to good opportunities and good people. Average ideas are everywhere, and they try to pull you in. The more successful you are, the more people will want to work with you. If you start saying yes to average ideas, you quickly lose the space and time you need to execute on great ones.

What I’m Reading

Even though women differ from apes in that they lack body signals of fertility, they make up for this through the clothes they wear. American university students were photographed at different points in their menstrual cycle as determined by self-report and urine tests. Judges of both genders were then asked to pick out the photos in which these young women seemed to “try to look more attractive.” It turned out that efforts to enhance their appeal changed with the cycle. Around their ovulation peak, the pictured women wore fancier, more fashionable clothing and revealed more skin. An Austrian study found a similar tendency. Investigators concluded that fertility unconsciously pushes women to boost their appearance and ornamentation.

— Frans de Waal, Different: Gender Through the Eyes of a Primatologist

Tiny Thought

The best way to learn something is to need that something. Learning when you don't really need to is a good way to give up early.

Before You Go…

If you’re finding this newsletter valuable, share it with a friend, and consider subscribing. If you aren’t ready to become a paid subscriber yet, but feel like I’ve done a good enough job writing today’s issue, you can also support me by buying me a cup of coffee. ☕️

Until next Sunday,

Abhishek 👋

PS: All typos are intentional and I take no responsibility whatsoever! 😬