Humour Might Be the Quickest Way to Demonstrate Intelligence

Or, Schrödinger’s cat walks into a bar… or does it?

I’ve often thought that humour might be one of the quickest ways to show how smart someone is. A joke told at the right moment or a clever line can tell you a lot about how a person thinks.

It shows how they see the world, how they make connections, and how they understand the people they’re talking to. Humour isn’t just about making people laugh; it’s about seeing things from a different angle and getting others to do the same.

IT ISN’T JUST ABOUT QUICK WIT, IT’S ALSO ABOUT EMPATHY

What makes humour seem smart, I think, is how it requires quick thinking. When you make a joke that hits just right, it’s not just about the cleverness of the punchline—it’s the way that joke dances with nuance.

Humour demands a kind of sensitivity to language, context, and the delicate play of social dynamics. There’s a lot happening beneath the surface, a kind of mental choreography. You have to understand not only the words you’re saying but also the unspoken rules of the room. The people in it. The moment. The timing. If you can read all of that, and still get the joke across, I think you’re doing something that requires a pretty high degree of cognitive complexity.

Take wordplay, for example: a pun like “I’m reading a book on anti-gravity—it’s impossible to put down.” It’s not high art, sure, but it plays with language in a way that feels clever.

Puns and good use of language makes you smile not just because of the idea, but because of how neatly it’s packaged. There’s something deeply satisfying about a well-placed pun, almost like you’re getting away with something—like the joke is a little secret shared between the speaker and the audience. The beauty of wordplay is that it’s not just about what you say, but how you say it. It’s linguistic mischief, a clever manipulation of language that makes the humour feel a bit more sophisticated, a little more cerebral.

In a way, humour is really a team effort. It needs an audience, even if it’s just your mom. You need someone to understand and appreciate the joke. So being funny isn’t just about having quick wit; it’s also about empathy—knowing what people will get, what will click with them.

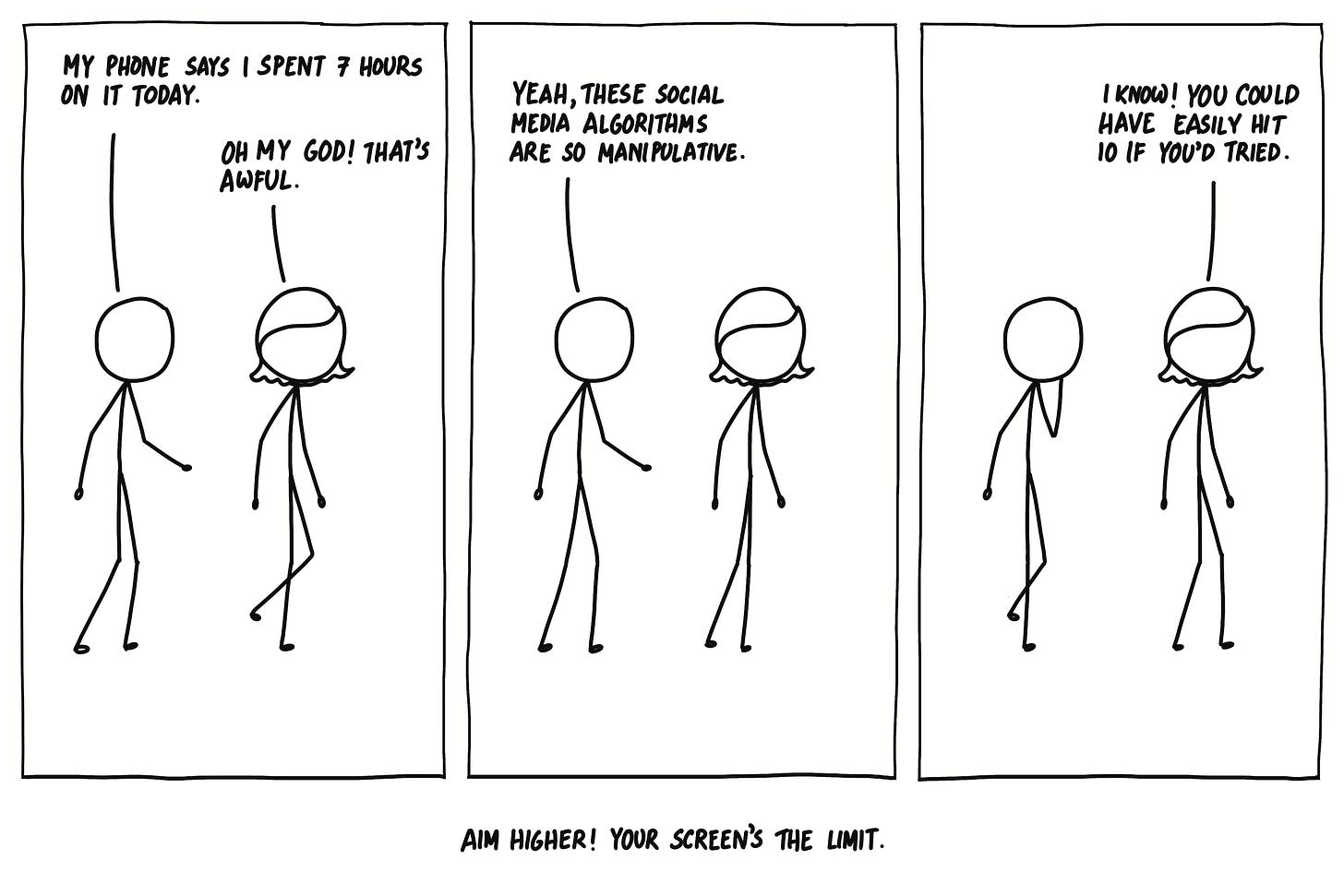

On that note, observational humour might be the most democratic form of comedy. Anyone who’s driven on a highway can laugh—or wince—at the observation that anyone going slower than you is an idiot, and anyone faster is a maniac. It’s funny because it’s true, but also because it holds a mirror up to our own, frankly ridiculous, self-centredness.

YOU SEE WHERE THE SETUP WAS GOING, AND THEN—BAM!

A good joke, I think, has a structure—an architecture, of sorts—that makes it work. It starts with the setup, of course. This is where the foundation is laid: the context is introduced, the characters or situations are revealed, and the audience is invited into the world of the joke. It’s as if you’re giving them a key to unlock the door, but the door has to look like it leads somewhere predictable, even if you know it won’t. Take, for example, a classic joke setup like: “Why don’t skeletons fight each other?” At this point, you’re expecting something about bones, maybe something about being too fragile.

The magic happens, though, in the punchline. “They don’t have the guts.” It’s like stepping off a curb into a pothole you didn’t know was there. You see where the setup was going, and then—bam!—it’s not where you thought it would go at all. That sudden, unexpected shift is the essence of humour. A big part of why some jokes land so well is because they rely on incongruity. And there’s something beautifully simple about it, too.

The punchline isn’t long-winded or complicated. It’s like a good song—it doesn’t need to drag on for minutes. A good punchline is short, to the point, and it hits. The humour doesn’t come from the buildup, but from how much it contrasts with what you were expecting. You think you know what’s coming, but you don’t. And when that shift happens, it’s like something clicks in your brain, and laughter just spills out.

Then there’s timing, which I’ve come to think of as the unsung hero of comedy. A good joke isn’t just about what’s said, but when it’s said. The best jokes give you a moment to sit with the setup before it drops the punchline. It’s all about pacing, really—letting the tension build before releasing it with that one perfect line. That moment of pause? It’s not just suspense; it’s an invitation. It lets you catch up with the joke before it completely unravels the expectation you had.

Here’s the thing I’ve learned: jokes that resonate are the ones that tap into something familiar, something shared. It’s the common experiences, the universal truths, that make humour feel so comforting. When you hear a joke about how much you hate small talk or how confusing relationships can be, it’s funny because it’s true. It feels like someone just voiced the thoughts that were already bouncing around in your own head. The best jokes, it turns out, aren’t just funny—they’re relatable.

THE KIND OF HUMOUR THAT MAKES YOU WINCE A LITTLE EVEN AS YOU CHUCKLE

The brand of humour that includes satire and irony feels like a kind of intellectual exercise—twisting a common idea into something unexpected, for example, “The squeaky wheel gets the grease, but the silent one often gets replaced.” It’s not just funny; it’s a reminder that speaking up gets attention, and silence often leads to being overlooked.