Where Does Morality Come From?

Or, why sometimes you can’t explain why something feels wrong

👋 Hey there! My name is Abhishek. Welcome to a new edition of The Sunday Wisdom! This is the best way to learn new things with the least amount of effort.

It’s a collection of weekly explorations and inquiries into many curiosities, such as business, human nature, society, and life’s big questions. My primary goal is to give you some new perspective to think about things.

A request: If you like this essay, could you do me a favour and hit that 🤍 heart so that it becomes a ♥️ heart? This helps me understand what kind of topics I should write more about. This also signals Substack that more people should read this essay.

One more thing: I’m trying to make a more conscious effort to personally know all of you. If you are interested in chatting over a video call, my calendar is open. Looking forward!

Q: Is the sense of morality universal among all human beings?

I’m going to start off with a story from Jonathan Haidt’s The Righteous Mind. It’s kind of a weird story, so consider this a trigger warning. Pause for a bit after you’ve read it and decide whether the people in the story did anything morally wrong.

“A family’s dog was killed by a car in front of their house. They had heard that dog meat is delicious, so they decided to cook it and eat it for dinner. Nobody saw them do this.”

If you’re like me, there’s a good chance you felt an initial flash of disgust. But if you really think about it, you might struggle to find a logical explanation to justify why what they did was morally wrong.

The dog was dead already, so they didn’t hurt anybody. And it was their dog, so it was upto them whatever they wanted to do with the carcass. Nobody saw them, so no one was emotionally distressed either.

If I push you to make a judgement, you’d probably say something like this:

Fair point. Now, here’s a bit more challenging story. Again, trigger warning!

“A man goes to the supermarket once a week and buys a chicken. But before cooking the chicken, he has sexual intercourse with it.“

Once again, no harm is done (the chicken is already dead) and nobody else knows about it. But now the disgust is even stronger, and the action just seems much much more degrading. But again, does that make it morally wrong?

You’d again probably say it feels wrong for someone to have sex with a chicken carcass and then eat it, and I’d agree.

If you break the rules of a game to gain an upper hand, we would all agree that it’s immoral. It’s an easy guess because you are harming your opponent unfairly.

But from an early age, we recognise that certain rules — such as rules about clothing, food, and many other aspects of life — are mere social conventions, which means they are arbitrary and malleable.

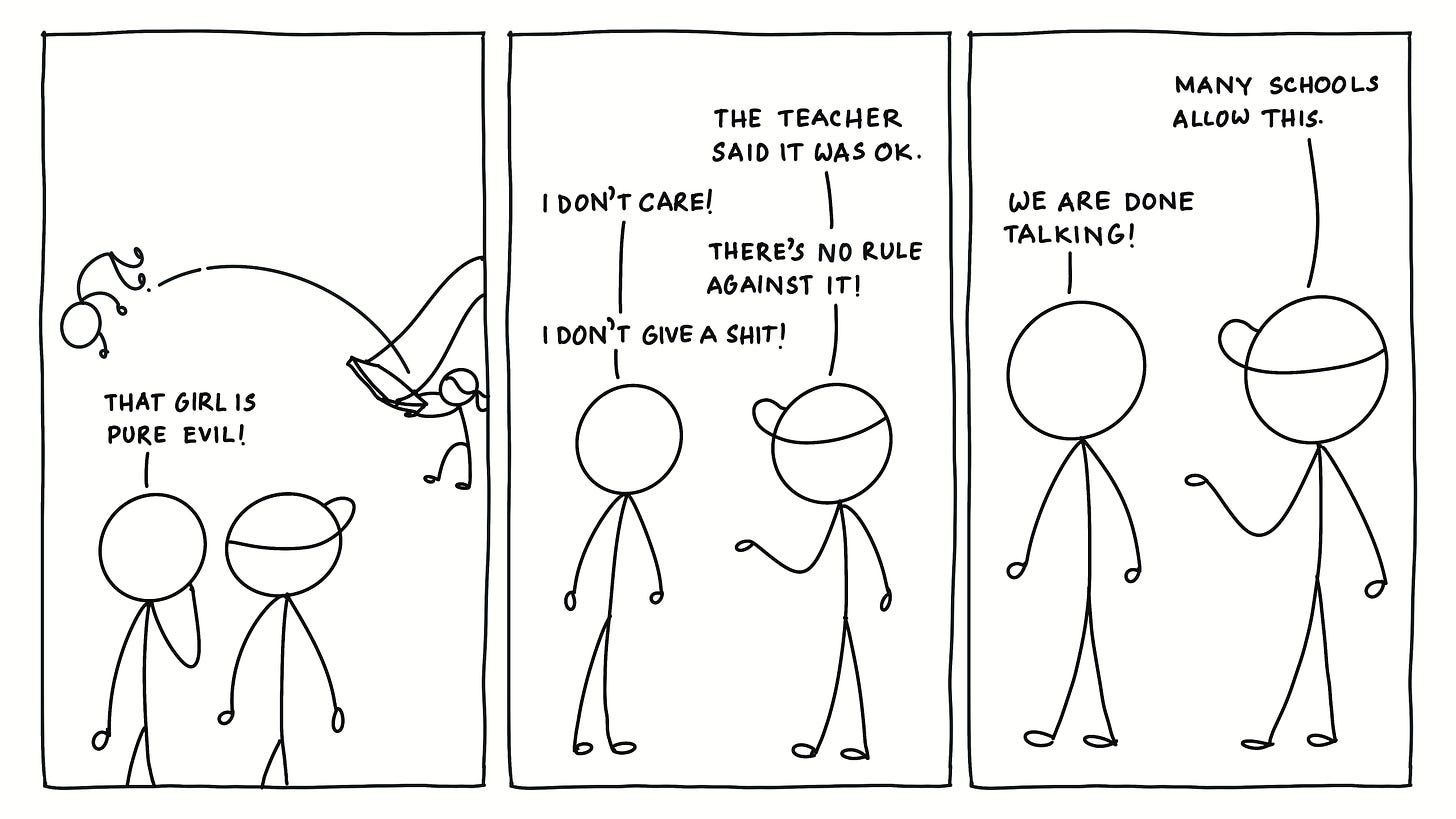

For example, if you tell the story of a child attending school without a uniform despite the dress code, many children would likely deem this unacceptable. But if you mention that the teachers permitted it, the reaction would change.

But if you ask the same kids about actions that harm others, the response differs, regardless of teacher permission or school rules.

When harm is involved, it’s usually very clear what is moral and what is immoral. But when you follow social conventions too much for too long, they become cultural conventions, and that’s when things get a little blurry.

For example, following are some actions that most liberal and modern societies would say are wrong, but a lot of patriarchal societies would be okay with:

A young married woman went to see a movie with her friend without informing her husband. When she returned home her husband said, “If you do it again, I will beat you black and blue.” She did it again; he beat her black and blue.

A man had a married son and a married daughter. After his death his son claimed most of the property. His daughter got little.

Similarly, following are some actions that most eastern cultures would scoff at, but it’s common in western cultures.

A financially comfortable middle-aged man places his elderly parents in a nursing home instead of having them reside with his own family.

A comedian takes the stage at an event and openly ridicules various religions, races, and deities.

In all the the above cases, harm is caused in some form. But they may not be considered immoral in certain cultures because they abide by the norms of that society. As The Joker says in The Dark Knight, “Because it’s all… part of the plan.”

The thumbrule is this: if something causes harm, it’s most probably immoral, unless it abides by the cultural norms of the society.

These moral conundrums usually start off with some sort of emotional reaction. When you encounter a stimulus, your brain constructs an emotion by integrating all kids of information.

For example, if you see a snake, your brain might take into account your past experiences with snakes, the context in which you see the snake, and physiological responses such as increased heart rate and sweating. These inputs are combined to construct the experience of fear or anxiety. But if you are a zoologist and spend your weekends catching rare snakes in the Everglades, your brain would construct an experience of excitement and thrill.

Similarly, when you see someone eating their dead dog, or having intercourse with a dead chicken, your brain integrates various factors such as cultural upbringing, personal experiences, and social context to construct a cognitive response and emotional reaction.

But when asked to justify this reaction, you are morally dumbfounded — rendered speechless by your inability to explain verbally what you know intuitively. Your plight is something like this:

Even though you try to find a good reason, this trying is not about finding the truth. It’s about finding reasons that match how you first felt. You see, the reactive part of your brain (System 1) had deemed the act immoral the very moment you read the story, and now the reflective part of your brain (System 2) is left struggling to validate this kneejerk assessment. Whatever reason you eventually come up with, it most likely won’t be the truth.

Our sense of morality is nothing but a concept of how we think things ought to be. It’s not innate, but is constructed from various direct and indirect life experiences. It’s not universal, but varies from culture to culture. In other words, it’s made up.

Before You Go…

If you’re finding this newsletter valuable, share it with a friend. Also, consider subscribing. If you aren’t ready to become a paid subscriber yet, you can also give a tip by buying me a coffee. ☕️

I’ll see you next Sunday,

Abhishek 👋

PS: All typos are intentional and I take no responsibility whatsoever! 😬

I would guess religious beliefs would feed system 2.....