The Limitations of Our Convictions

Or, the stronger the claim, the more rigorous should be the research

👋 Hey there! My name is Abhishek. Welcome to a new edition of The Sunday Wisdom! This is the best way to learn new things with the least amount of effort.

The Sunday Wisdom is a collection of weekly essays on a variety of topics, such as psychology, health, science, philosophy, economics, business, and more — all varied enough to turn you into a polymath. 🧠

The latest two editions are always free, the rest are available to paid subscribers. Now… time for the mandatory plug!

Today, I’m trying something new. This essay is shorter than my usual length but it is illustrated with stick figures. They look like they’ve been drawn by a four-year-old, but they’ve actually been drawn by an adult, i.e., me.

I would love to know what you think of them. Reply to this email or share in the comments. (I do want to continue adding them in future essays, but no promises as of now. This is an experiment for now.)

This week I couldn’t post the other sections of the newsletter because I exceeded Gmail’s recommended limit. I’m gonna take this opportunity to post them on Substack Notes instead. Keep an eye out. Ciao!

On to this week’s essay. It’s about 1,000 words.

Q: What does it really mean to be objective?

The mistakes we make when we make decisions, both individually and as a society, often happen because we don’t fully understand the importance of following scientific standards. We rely too much on our own convictions even though they suffer from many limitations.

Personal beliefs and feelings maybe important, but they’re not enough to prove something scientifically. People often forget this!

It’s crucial to have solid evidence, test things together with other people, and be able to repeat and confirm your findings whenever possible. Otherwise, you would be like a man walking on a tight rope — forever weary of falling off whenever the balance of arguments shift.

Now, whenever we talk about scientific standards, we have to talk about the concepts of “objective” and “subjective” truths. Thankfully, philosophy has some direction to offer. Let’s take a moment to explore how the philosopher Immanuel Kant sheds light on the significance of these concepts.

So according to Kant, objectivity is any knowledge that can be proven and understood. Unlike speculations, point-of-views, and conspiracy theories, scientific statements are “objective” because they can be tested and verified by anybody (provided they have the necessary means, equipments, and knowhow), no matter their personal biases or weird quirks.

Although, another equally famous philosopher Karl Popper may slightly differ from Kant on the complete justifiability or proof of scientific theories (according to Popper, scientific theories can never be proven, only disproven), but he would definitely agree with Kant that scientific theories are indeed testable.

This basically means anyone can put any scientific theory to test and see if it holds up.

On the flip side, Kant’s idea of “subjectivity” is all about our own personal feelings and how convinced we are about something. These feelings can vary from person to person and might not always be set in stone.

Our personal experiences and backgrounds shape our preferences. That’s what makes taste subjective – it’s unique to each individual and can’t be proven right or wrong. Think about your taste in music. You might love Bollywood music, while your friend can’t stand it and prefers classical tunes.

The same can be said for liberal arts such as literature, philosophy, sociology, fine arts, etc. Unlike physics, these are subjective and lack any objective truth. Each view or opinion is unique to a certain school of thought and it’s not possible to establish one school of thought is right and another is wrong.

The problem arises when you give a lot of value to personal opinions in objective truths.

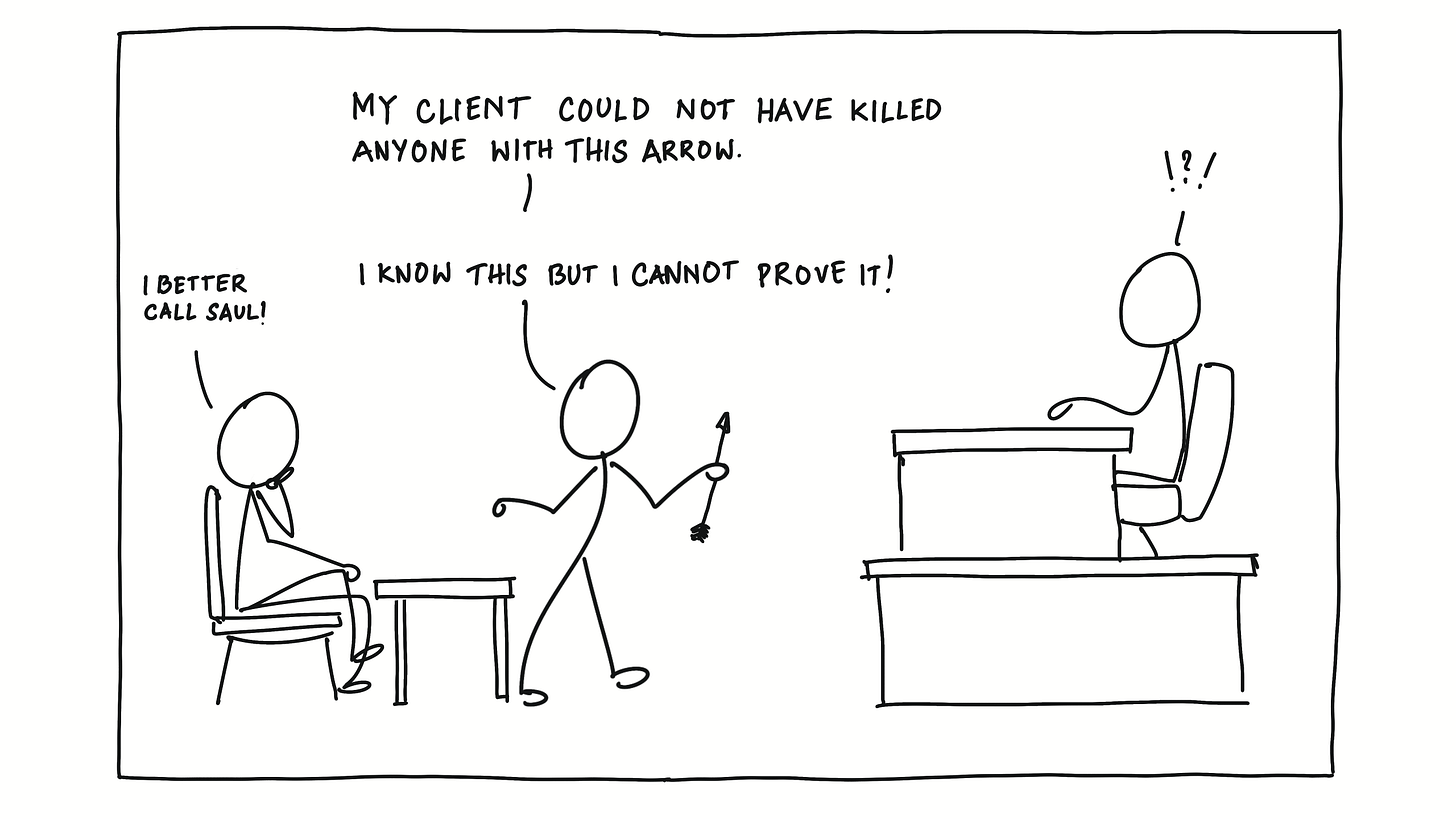

When it comes to objectivity, personal convictions and gut feelings aren’t enough to prove something. Scientific claims need hard evidence and testing to back them up. Otherwise you are like a lawyer who strongly feels the client is innocent but has no evidence to prove it.

Objectivity demands facts, experiments, proof, and has no place for subjectivity.

Another problem arises when you hear or see something that is subjective and consider it to be objective (for example, communism is the best system to run a nation). Or, worse, you hear something that has never been tested or has already been debunked several times and yet you consider it as objective truth without verifying it yourself.

We especially make this mistake when we fall for the words and advice of social media gurus. Just because someone says or strongly feels about something doesn’t make it true.

For example, to really know if some rare miracle cure works, you need to read some material about it. If you can find a lot of study that confirm its efficacy, you can confidently say that it indeed works. (Although, if decent research has already been done on it, there’s a strong chance it isn’t rare.)

Instead of conforming evidence, if you see a mix of both false positive and false negative results in the studies, or that it’s mired with controversy, you can consider it to be still in development, and not a foolproof cure as it claims to be.

And if you can find no study at all, then either it’s indeed a new kind of cure that nobody knows about (however, chances of that happening are very low), or it’s just a fluke.

In any case, consuming content that is optimised for eyeballs isn’t enough to believe in something. It’s safer to be sceptical of everything that is popular. That’s why perhaps the most important skill of a thinker is knowing when to trust.

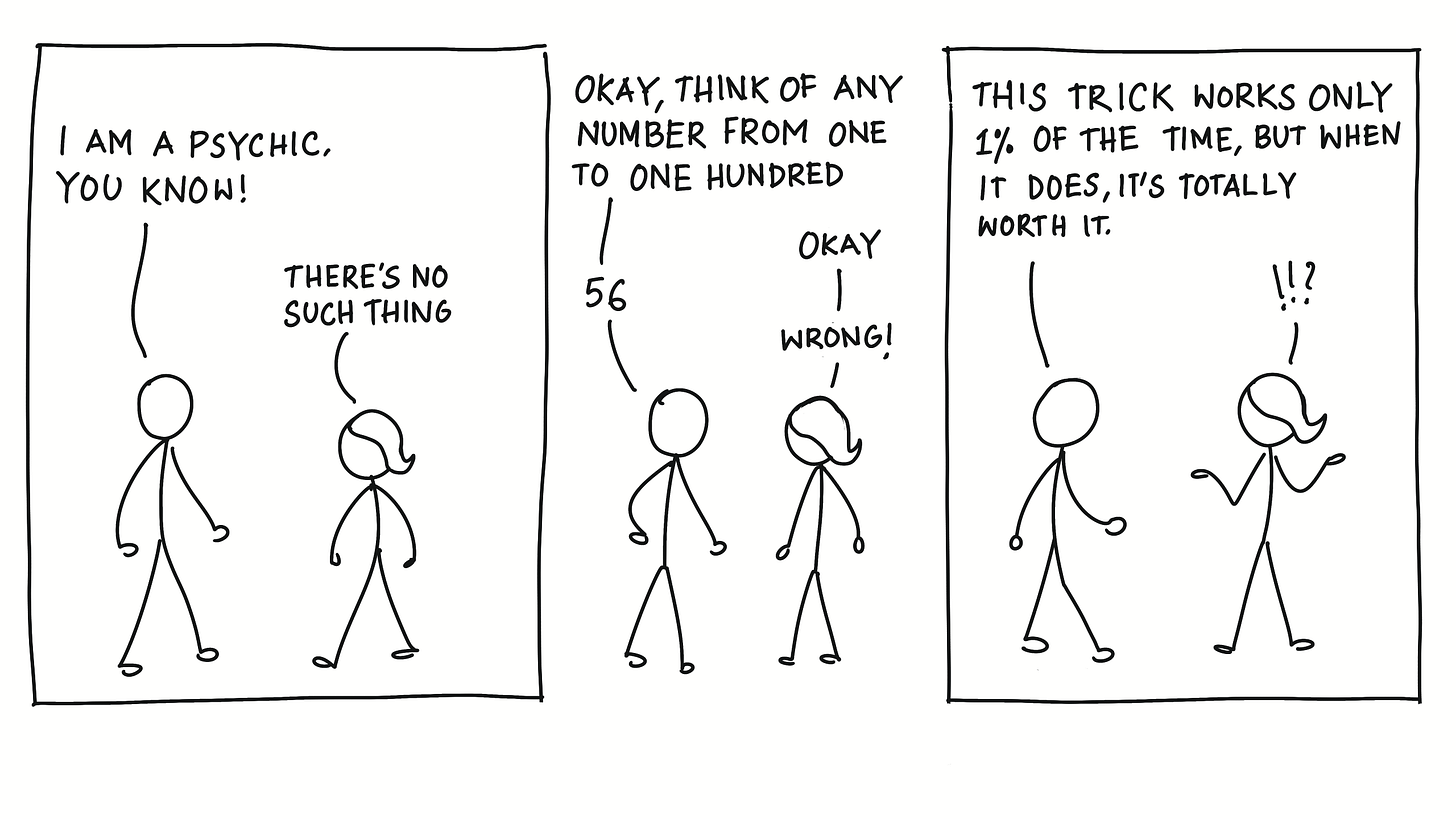

Now, you don’t need to do this every time somebody claims something new; otherwise you won’t be able to do anything at all. It’s especially not worth the effort if the claim is puny. A general rule of thumb is: the stronger the claim, the more rigorous should be the research. More than anything else, scientific thinking is about rigour, followed by repeatability.

In experimental physics, scientists often stumble upon mind-boggling effects in the lab. But they don’t count as scientific discoveries unless they can be reproduced by anyone following the right procedures. It’s like a magic trick that needs to work every time for everyone.

Personal experiences are important to us, but when it comes to science and the quest for objective truth, we cannot rely on them confidently.

We need hard evidence and the ability to test and verify things. If we cannot verify ourselves, the next best thing is to see if others have verified it independently, and if there’s a consensus in the scientific community.

Even after all this, there might still be some room for error, but the odds would be much more in your favour.

Before You Go…

If you’re finding this newsletter valuable, share it with a friend, and consider subscribing. If you aren’t ready to become a paid subscriber yet, you can also buy me a coffee. ☕️

I’ll see you next Sunday,

Abhishek 👋

PS: All typos are intentional and I take no responsibility whatsoever! 😬