The Problem With Absolute Freedom

Or, freedom granted is freedom tolerated

👋 Hey there! My name is Abhishek. Welcome to a new edition of The Sunday Wisdom! This is the best way to learn new things with the least amount of effort.

The Sunday Wisdom is a collection of weekly essays on a variety of topics, such as psychology, health, science, philosophy, economics, business, and more — all varied enough to turn you into a polymath. 🧠

The latest two editions are always free, the rest are available to paid subscribers. Now… time for the mandatory plug!

My original plan last week was to post the usual supplements (such as Today I Learned, Tiny Wisdom, Timeless Insight, etc.) as Notes, but to be honest, I never remembered to post them. I’ll try to do a better job this week.

Now, on to this week’s essay.

I’ve been taking a break from both neuroscience and philosophy and have been reading Tim Urban’s brilliantly written and illustrated What’s Our Problem?. It’s just fantastic, to say the least. I’ve borrowed the core idea of this essay from the book. Hope you enjoy it!

This essay is about 1,100 words.

Q: What if we had absolute freedom? Would that solve all of society’s problems?

There’s a misconception that absolute freedom is the ultimate solution to all sorts of societal problems. But the truth is that absolute freedom is NOT at all desirable. 100% freedom is not just imperfect, it’s also a sureshot recipe for complete anarchy.

Take the animal world for example. There are no morals, no principles, and no one to make sure things are fair. The rule is simple: Everyone has full freedom to do whatever they want to.

In the wild, when a wolf meets a rabbit, if the wolf wants to eat the rabbit, it can — as long as it can catch it. And if the rabbit prefers to keep itself alive, it can — as long as it can run fast enough. That’s all there is to it.

Since both the wolf and the rabbit have 100% freedom to do as they please, whether the wolf gets to have the rabbit for dinner or whether the rabbit lives to see another day doesn’t really depend on freedom; it depends on who has more power.

Thus, the real rule is: Everyone can do whatever they want, if they have the power to do so.

Let’s call this the Jungle Law.

Now, picture a society governed by the Jungle Law. You’re living with 100% freedom, and all of your fellow citizens are also living with 100% freedom.

If everyone gets along all the time, this is great. The problem though is that throughout history, people have struggled to get along consistently.

So, what happens whenever any kind of conflict arises? The bully wielding the bigger stick dictates the outcome. And if the bully suddenly decides to restrict your freedom, there’s nowhere to turn and no one for you to appeal to.

Then, a bigger bully comes along and gets their way. After a few rounds of power struggle, the biggest bully of all establishes the rules for everyone to follow. Depending on who that person is and how they feel about individual freedom, you may find yourself with no freedom at all.

Under the Jungle Law there are only be a handful of (freedom) winners and lots and lots of (freedom) losers.

But what if we modify the Jungle Law into a compromise? Instead of “Everyone can do whatever they want if they have the power to do so,” it becomes, “Everyone can do whatever they want as long as it doesn’t harm anyone else.”

Let’s call this the Civil Law.

Under the Civil Law, you basically exchange the “freedom to oppress others” for the “freedom from being oppressed.”

Pretty good trade, right? To be absolutely clear, under the Civil Law, no one would be completely free, but everyone would be mostly free — and that’s much much better.

The Civil Law has two aspects baked into it. The first part — everyone can do whatever they want — describes what people can do, i.e., their rights. The second part — as long as it doesn’t harm anyone else — describes what they cannot do, i.e., their restrictions.

The Civil Law not only protects the rights of the citizens but also enforces the restrictions. This creates a pretty humane place to live in. Thankfully, this is how most modern governments are designed.

Another important tenet of the Civil Law is that the rights and restrictions of citizens are mutually exclusive. In other words, the freedom granted to a citizen is something they would have to tolerate in others. Likewise, safeguarding citizens from certain behaviours would automatically prohibit those behaviours.

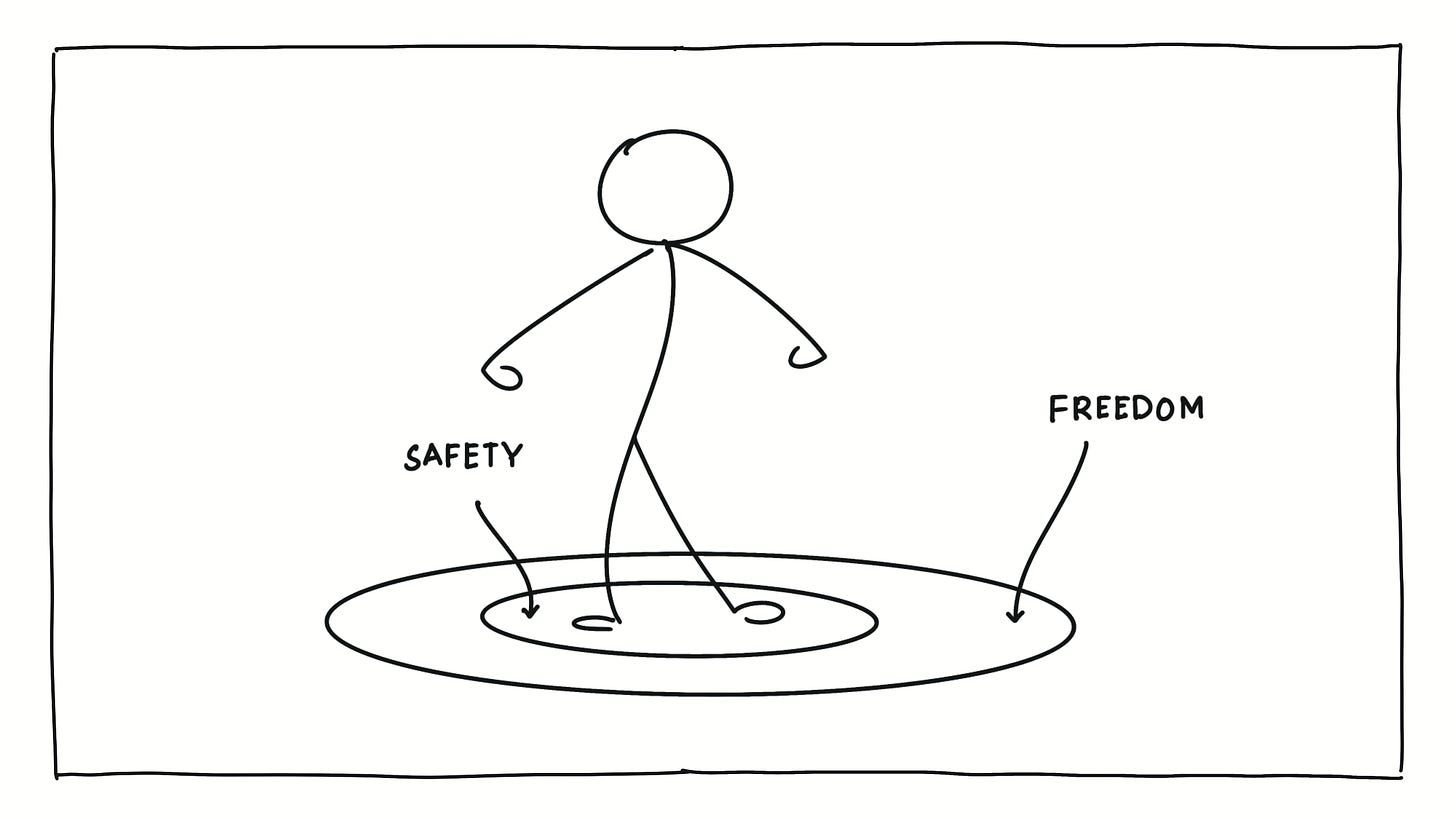

We can imagine this as two circles surrounding every citizen.

The outer circle provides substantial freedom, a luxury rarely enjoyed under the Jungle Law. However, the moment someone’s outer circle encroaches upon another person’s inner circle, it becomes a violation of the law and is dealt with accordingly.

This not only provides freedom and safety but also generates a brilliant side effect: economic productivity.

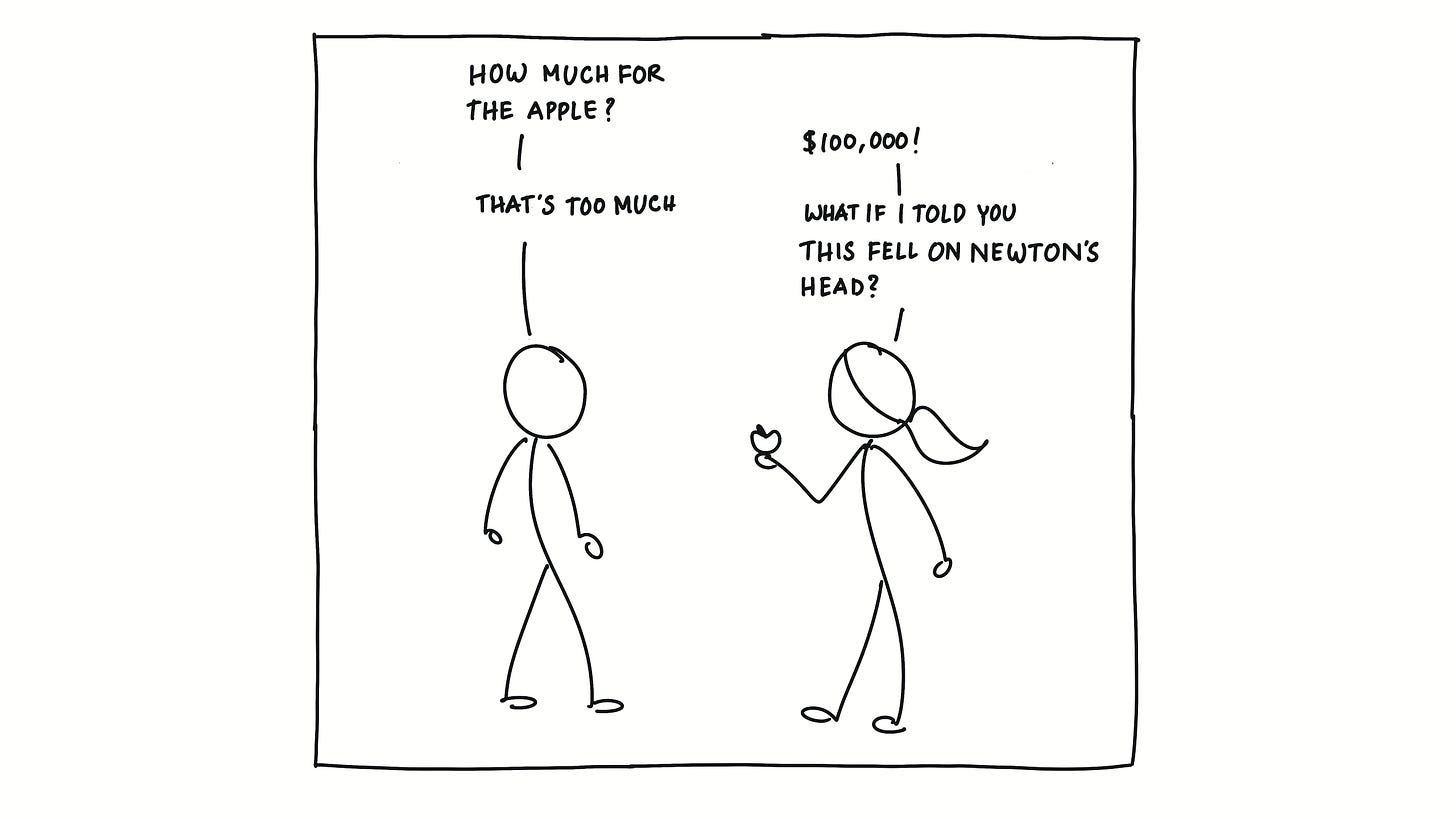

Unlike the Jungle Law, under the Civil Law, you cannot use the power of a stick to get your way. Instead, you’d have to do so with persuasion, i.e., a carrot.

For instance, if I want something from you, my only option is to convince you to voluntarily provide it by appealing to your self-interest. This requires offering incentives that you value more than what I seek from you.

By removing the “stick” from the picture (or, rather, imposing severe penalties for its use) the game shifts from a contest of who can be the scariest, the most dangerous, and the most intimidating, to a contest of who can provide the most value.

Under the Civil Law, citizens can compete for wealth by obtaining jobs or starting businesses, as long as they can persuade others to exchange money for their offerings. Similarly, they can compete for political power by persuading others to vote for them.

Human behaviour can be boiled down to a simple operation.

Interestingly, human nature remains the same in both the Jungle Law and the Civil Law, just that the Civil Law forces human selfishness to become an inexhaustible, self-regulating, self-propelling engine that constantly provides value.

As Adam Smith aptly put it, “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.”

This is capitalism in a nutshell.

If you think about it, today’s antibiotics, aeroplanes, mobile phones — luxuries the wealthiest people of the medieval times couldn’t have dreamt of — are testaments to the effectiveness of the Civil Law.

But… all is not so rosy after all, especially when you’re dealing with humans.

While the Civil Law represents the ideal way to conduct amicable affairs, every individual carries within them a piece of primitive software rooted in the Jungle Law. Even if human selfishness is restrained and confined under the Civil Law, it may not remain contained indefinitely.

Taking the human out of the jungle is one thing. Taking the jungle out of the human is quite another.

No matter how many written rules exist, it is the citizens’ ability to uphold norms that determines a society’s fate and prevents its descent into the Jungle Law. This is why a society’s history is, above all, the story of its struggle against itself.

Before You Go…

If you’re finding this newsletter valuable, share it with a friend. Also, consider subscribing. If you aren’t ready to become a paid subscriber yet, you can also give a tip by buying me a coffee. ☕️

I’ll see you next Sunday,

Abhishek 👋

PS: All typos are intentional and I take no responsibility whatsoever! 😬