👋 Hey there! Welcome to a new edition of The Sunday Wisdom! My name is Abhishek. I read a lot of books, think a lot of things, and this is where I dump my notes and (so called) learnings.

I mostly write to educate myself; this is kind of my Feynman Technique in action. But if you like my writing, I would say this little hobby of mine just became a bit more purposeful. Now… time for the mandatory plug!

But seriously, if you are facing trouble completing the subscription above, you can alternatively make a pledge on Patreon (if you are sooo keen). Pledge whatever amount you want and I’ll unlock paid posts for you. Deal?

Enough talk! On to this week’s essay. It’s about 3,000 words.

Q: Why can’t a country print unlimited money to get rich?

Let me tell you two stories — one apocryphal (has doubtful authenticity, but widely circulated as true, kind of like Henry Ford’s comment about faster horses) and one true. They are very similar in nature and they happened about 80 years apart.

See, after World War I, Germany was burdened with making amends for the war they had just lost so badly. Their economy was shot and the German government had no money.

In a desperate attempt to pay off their debts, they came up with this ingenious idea of printing large amounts of money. The problem was… even though they had good knowledge of printing (they were after all the descendants of Johannes Gutenberg, the OG of printing technology), they had poor knowledge about fundamentals of economy.

If you have read (and remember) the first part of this series on capitalism, you’d very well know by now why having too much money does not necessarily mean too much fun, especially when economic productivity doesn’t increase hand in hand.

So… eventually the inevitable happened — a rapid devaluation of the German currency. Too much money in supply but nothing much to buy.

As prices skyrocketed, people were forced to carry large amounts of cash just to buy basic necessities like bread and milk. In fact, inflation became so extreme that it was not uncommon for prices to double or even triple in a matter of hours, kind of like Bitcoin.

This one time the German currency was so worthless that people were forced to transport their money in wheelbarrows just to buy basic goods.

So… the story goes like this. One fine day a Mr. Schneider (who later became famous as the “wheelbarrow man”) brought a wheelbarrow full of money to a bakery in order to buy a loaf of bread. However, while he was inside the bakery, someone stole his wheelbarrow, leaving Herr Schneider with a pile of worthless cash and no wheelbarrow to carry them back home.

It’s like somebody stole a bank vault, but left all the money behind. Funny! (Also, come to think of it, Herr Schneider should have been called the wheelbarrowless man instead; but who’s keeping tabs!)

Now… time for the second story. This one has always fascinated me; probably because it’s less of an economic story, and more of a story of human stupidity (which apparently has no limits).

When Zimbabwe gained its independence from the United Kingdom in 1980, the newly introduced Zimbabwean dollar was initially more valuable than the US dollar at the official exchange rate.

Fast forward twenty-years and one-trillion Zimbabwean dollar was worth just about ten US dollar. Welcome to the land of hyperinflation!

See, in its early years, Zimbabwe experienced strong growth and development. Wheat production for non-drought years was proportionally higher than previous years, and the tobacco industry was thriving. Economic indicators for the country were strong.

But in the early 2000s, the government of Zimbabwe under the leadership of President Robert Mugabe got its head stuck inside its ass and wasn’t able to get it out for quite some time.

For starters, the government instituted land reforms intended to evict white landowners and place their holdings in the hands of black farmers. The problem? The black farmers had zero experience in agriculture. The farms simply fell into disrepair or were given back to some Mugabe loyalists, who were equally incapable. As a result, the country experienced a sharp drop in food production and in all other sectors over the next decade.

Seeing this, the banking sector also decided that it was time to put its pants down and give up. As banks collapsed, farmers were unable to obtain loans for capital development. Food output fell by forty-five percent while manufacturing output fell by upto sixty-two-percent in the next ten years. Unemployment also had risen to eighty-percent. In other words, economic productivity was down by almost one-hundred-percent.

However, the Mugabe government was very cool headed. They didn’t pay any heed to the economic deterioration and was busy with a side project — funding the Second Congo War (aka African World War).

But the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe decided to step in. It was time for them to act. They responded to the dwindling value of the currency by doing the most sensible thing — repeatedly arranging the printing of further banknotes, often at great expense, from overseas suppliers.

One report suggests that in 2008, a decade after the economy had gone to the docks, a Munich-based company (zee Germans again) was receiving more than five-hundred-thousand US dollars a week for printing bank notes equivalent to one-hundred-and-seventy-trillion Zimbabwean dollars a week.

At one point, the US Ambassador to Zimbabwe predicted that inflation would reach 1.5 million percent. In June 2008 (almost a decade after the government got its head stuck inside its ass), the annual rate was 11.2 million percent, 7.5x more!

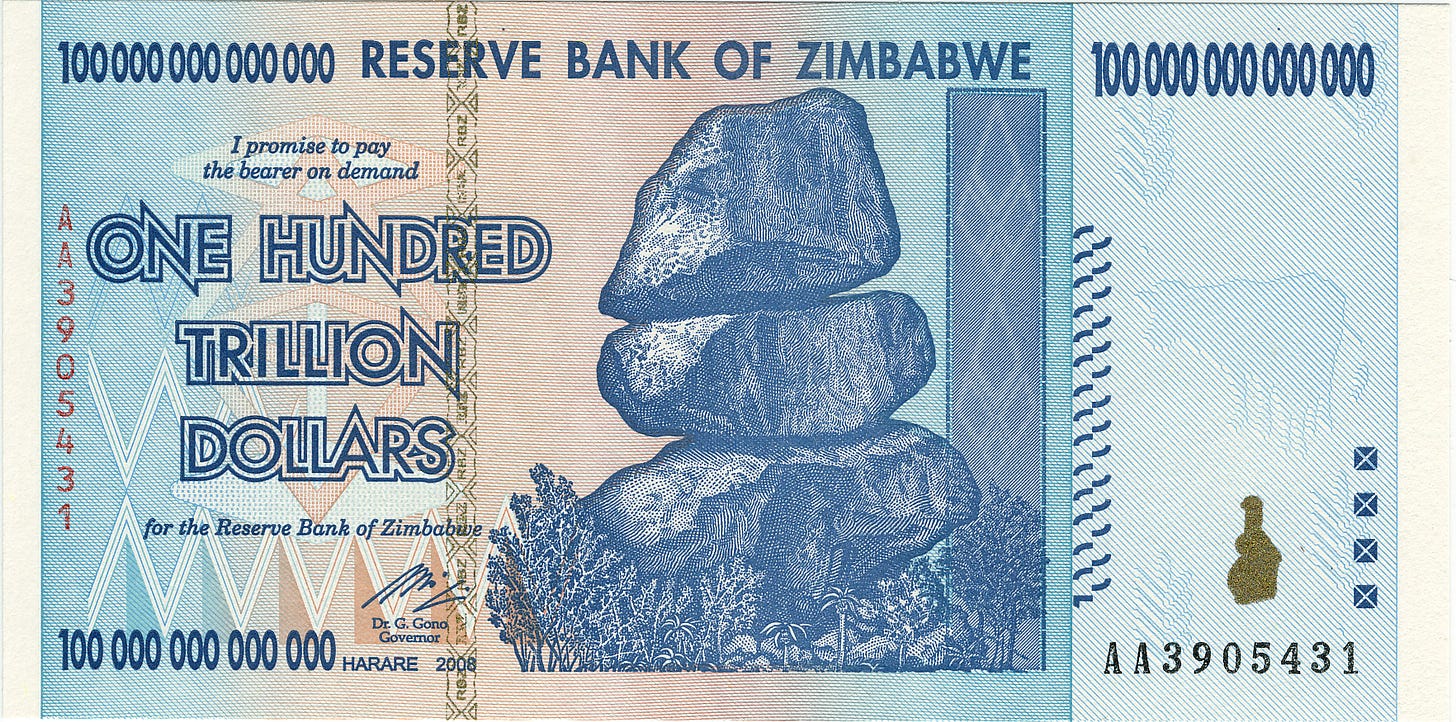

The largest denomination of a Zimbabwean banknote the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe had printed was one-hundred-trillion. One. Hundred. Trillion. That’s a one with fourteen zeros after it. Let that sink in for a moment.

The funny thing is that ATMs were incapable of accepting so many zeros, and started giving a “data overflow error” that stopped common folks from withdrawing money. Systemic incompetence at its peak!

But the saddest part is that, even now, the story isn’t over. In April 2009, Zimbabwe finally decided that they were running out of space to store all these money, and stopped printing its currency. Currencies from other countries were used instead. In mid-2015, Zimbabwe announced plans to have completely switched to the US dollar by the end of that year.

In June 2019, the Zimbabwean government reintroduced a new native currency (the fourth time in the last decade), the Zimbabwe dollar (one ZWL was worth ten-trillion original dollars), and announced that foreign currency was no longer legal. People kind of started to have the feeling that good times have finally started rolling.

But by mid-July 2019, inflation had increased to one-hundred-and-seventy-five-percent, sparking concerns that the country was entering another period of hyperinflation.

In March 2020, thanks to COVID-19, with inflation above five-hundred-percent annually, a new task force was created to assess the currency problems. By July 2020, annual inflation was estimated to be seven-hundred-and-thirty-seven-percent.

If you (aren’t from Zimbabwe and) are having a bad day (rent is high, salary is low, prices are rising with every passing day, and what not), remind yourself of this story.

So… that was the story. Now let’s try to understand the mechanics behind it.

As we have learnt earlier, the economy works like a machine — when borrowing is easily available (interest rates are low), there’s an economic expansion. When borrowing isn’t easily available (due to high interest rates), there’s a recession.

As the economy wants you to borrow as much as possible, it doesn’t prefer keeping interest rates high for a very long time. As soon as inflation becomes slightly less of a threat, the central bank lowers interest rates to promote economic expansion.

But the problem is… when interest rates were high, even though people might have focussed on debt repayment for a while, debt didn’t completely go away. Debt only became slightly less potent. Debt is now waiting for the apt moment to strike back… with a revenge.

As soon as interest rates are low, people shift gears towards hedonism again. Instead of repaying, they start rejoicing. People always have an inclination to borrow and spend more instead of paying back debt. It’s human nature! Like Faust, we do prefer living our life to the fullest at present, preferring to pay a sizeable amount for it in future. As a result, spending grows, income grows, but so does debt; in fact debt compounds.

But unlike Faust, who at one point started doing good deeds in order to gain redemption, when it comes to us, we’re a bit lazy about that; we prefer to hit the snooze button and put it in the backburner. (Also, do you know what today’s money brokers — financiers, bankers, and the likes — call the repayment of a debt? They call it ‘redemption’, which means being absolved from your sins; and it’s not a coincidence.)

So… because we push it (borrow more, spend more, but produce less), over a long period of time, debt eventually catches up. Then one fine day, debt starts rising faster than income. Oops!

But… and this is the real shocker: despite people becoming more and more indebted over time, lenders put their foot on the gas and start lending more and more freely. Why? Just look at interest rates… they are low; just look at incomes… they are high.

Overall spending is high and the economy is doing very very good as a whole. It’s boom time and it would be stupid not to tap into it. Hence the rule of the season is: lend, lend, lend, which also means: borrow, borrow, borrow!

Of course… if you borrow more and more (and even if you use a bit of that to repay a part of your debt), technically you become more and more indebted everyday. This does sound stupid (and it is), but we don’t need to worry about it right now; there are much more important things we need to take care of at this moment. We just came out of a recession for god’s sake. There’s so much pent-up demand inside us that we need to fulfil first! We’ll worry about the debt later.

Now… with rising debt and so much borrowing happening like there’s no tomorrow, the central bank should increase interest rates again to stop this foolishness. And had it been a different time they would have most likely done that. But… the economy barely got out of a recession. It would be foolish to slow things down even before it got a chance to get back on its feet properly.

Low interest rates, mixed with rising income, along with a big dollop of optimism creates a highly explosive mixture. And this time people don’t just spend money on goods and services, they spend a big chunk of their borrowed income on financial assets as well.

Fresh out of a recession, this time people are also focussed more on growing their wealth, not just their living standards. Since it’s boom time, the future has only good things in store. People borrow huge amounts of money and invest heavily in stocks, housing, and speculative markets — all for a prosperous future.

When a lot of people do a lot of that, It sends asset prices soaring to dizzying heights. People feel wealthy (at least on paper). You might recognise this phenomenon by its more common term: bubble.

In the 1840s, railways were considered a revolutionary technology that would transform transportation and trade. Thousands of investors, from all walks of life, including businessmen, politicians, farmers, and even ordinary people, invested their money in railway companies of Great Britain and Ireland in the hope of getting rich quickly. The demand for shares skyrocketed, leading to a massive increase in their prices.

Around 2017–18, the price of Bitcoin increased dramatically, reaching an all-time high of nearly $20,000 USD per Bitcoin in December 2017, up from just a few hundred dollars a few years earlier.

The crypto bubble was fuelled by a combination of factors, including hype, speculation, and a belief that Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies would revolutionise the financial industry.

Many people, including both retail investors and institutional investors, poured money into Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, driving up their prices.

If you think about it, a bubble is kind of like an inflation. The difference is only in perception. Since you know the price of a piece of bread, when it becomes costlier (due to high demand), you get the same value but now you have to pay more. You know this only because you know the real value of a piece of bread. This means that your money has actually lost some of its value, i.e. inflation.

But in a bubble, you neither know the actual price nor value of an asset, and completely based on speculation and public frenzy, as it becomes more and more costly, you think it’s because the asset is actually much more valuable than what people thought before. Fun fact: it’s probably not.

A bubble happens because of public optimism… yes… but also because asset values are constantly rising precisely because of this bubble. People are buying, causing their prices to go up, and this is causing more people to buy (mostly driven by FOMO), increasing the price further. The loop is reinforcing.

Even though debt in the economy is accumulating, the rising (paper) income from the rising asset values allows free flow of borrowing. But this free flow of easy money obviously cannot continue forever. And it doesn’t. What goes up has to eventually come down crashing!

Within a few of years of this borrowing frenzy, debt becomes so humongous that banks start to tighten their lending rules. This makes people focus on debt repayments yet again. Spending goes down. And since one person’s spending is another person’s income, income begins to go down, thereby causing borrowing to go down as well. The downward spiral has just begun again, but this time it’s a big big one.

In the 1980s, Japan experienced a rapid economic expansion. Asset prices were increasing rapidly. People thought they would never go down and invested heavily. They eventually became overvalued, leading to an asset price bubble, particularly in real estate and stocks.

The thing about bubbles is that they eventually burst. And when they burst all the money invested disappears into thin air. It did for Japan in 1989, which lead to a period of economic stagnation that lasted for more than a decade. As a result, many Japanese companies and households found themselves with high levels of debt and non-performing assets, particularly in the banking sector.

In 1840s England and Ireland, many of these railway companies were not profitable and were backed by untested technologies and untried management. In addition, many of them were competing with each other, resulting in a duplication of routes and a significant increase in costs. As a result, many railway companies went bankrupt, and their shares became worthless, causing huge losses for investors. When the Railway Mania bubble burst, it lead to a severe economic recession in Britain and Ireland.

Similarly, in early 2018, the crypto bubble burst and the price of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies plummeted. This led to significant losses for many investors who had bought in at the peak of the bubble (most likely with borrowed money).

Now… it is important to note that bubbles burst all the time. But once in a while, when everything else is lined up, the bursting of a bubble at a very apt moment creates the recipe for a massive massive economic disaster. This happens roughly once in every 80–100 years.

Even though people are quick to blame the bubble for this failure, disasters aren’t that simple. Disasters don’t have any root cause; they happen regardless of it. For a disaster to happen, enough small errors need to line up, leading to a compounding effect via a chain reaction.

In an economy, this usually happens when debt has surpassed income, and now people are so much crippled by debt burden that they cannot borrow anymore even though interest rates are zero. At this very moment, if a bubble bursts (causing their assets to become valueless), economic mayhem is inevitable. Fun fact: a bubble always bursts at this very moment.

Here’s a quick rundown of things: As income falls due to less spending and more debt repayments, borrowers get squeezed. They can no longer borrow money to repay debt. Scrambling for money, so that they can repay some of their debt (so that they can borrow again), they are forced to sell assets. The technical term for this is: deleveraging.

But during a deleveraging, this sudden rush to sell assets floods the market — there are just too many sellers and not many buyers. This causes the bubble to burst, and at the same time spending goes into a freefall.

Next… the stock market collapses, the real estate market tanks, and then banks get into trouble as they see their money disappear. Something very similar had happened during the 2008 financial crisis.

Assets became worthless, the stock market crashed, banks collapsed, businesses cut spending, people lost jobs, income fell, social tensions rose, and the whole thing started feeding on itself.

This appears similar to a recession, and normally the central bank would reduce interest rates to promote borrowing and stimulate the economy. But… the difference here is that interest rates can’t be lowered to save the day anymore — they are already at the lowest.

On top of that, people are in so much debt that it would be foolish to lend them more. Also, fear has set in, and people don’t want to borrow anymore anyway. The future doesn’t look bright. Their investments have disappeared. People feel poor.

Right now, the one and only goal of the central bank is to reduce the amount of debt in the economy. This is when they start doing their second most important job: printing new money.

But the economy cannot be saved just by printing money (we know very well what happens when we decide to print unlimited money). So the central bank has to implement a few other savvy tactics to stabilise the economy.

Today I Learned

Youyou Tu is a Nobel laureate; the first Chinese (and woman!) pharmacist to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine (2015) for a discovery that has its roots in traditional Chinese medicine. She had isolated and characterised the compound artemisinin, still used to fight malaria.

Tu is also known as the “professor of the three no’s”: no membership in the Chinese Academy of Sciences, no research experience outside of China, and no postgraduate degree.

It all began in the 1960s when North Vietnam asked their Chinese allies to help them against the greatest and tiniest adversary in the war: the one-celled parasite Plasmodium. Mosquitoes carrying this parasite cause malaria, which was killing more soldiers on both sides than actual combat.

It’s worth noting that in the mid-60s, China was in the midst of the Cultural Revolution, a time in which intellectuals (especially those who asked too many questions) were persecuted and often tortured. Mao Zedong however needed capable researchers to find a solution to the pressing Malaria problem. So, calling up more than 500 people, he launched a covert effort called Project 523, after the day it started: May 23rd, 1967.

Tu had a lot of disadvantages — when she was recruited to work on 523 she had to leave her 4yo daughter in an orphanage, since her husband was detained in a labour camp — but she had an outsider advantage as well that made it easier for her to look in places others would not dare.

Before Tu, other scientists had reportedly tested 240,000 compounds searching for a malaria cure. But unlike her contemporaries, Tu was interested in both modern medicine and history, and was inspired by a clue in a recipe for medication made from sweet wormwood, written by a fourth-century Chinese alchemist. It led her to experiment (at first on herself) with a sweet wormwood extract known as artemisinin.

Artemisinin is now regarded as one of the most profound drug discoveries in medicine. A study on the decline of malaria in Africa attributed 146 million averted cases to artemisinin-based therapies between 2000 and 2015.

Timeless Insight

When someone comes to you for feedback, they usually say some version of, “Is this anything?” or “Do you like it?” or “How can I make this better?” But… even though they ask you for ‘feedback’, what they actually need might be something else completely.

For example, they may need validation (“Is this a stupid idea?”), or reassurance (“Tell me I haven’t lost my mind”), or confidence (“Do you think I’ll get there?”), or empathy (“I’ve put in a lot of effort but haven’t had a breakthrough yet.”).

If you give them a barrage of feedback; if you tell them how they can make something better by doing this and that, you’d be doing both yourself and them a huge disservice.

Although this feedback may look okay on paper — you are after all giving real actionable ideas — it may not necessarily help them get to where they want to be.

People have varying needs. They can often say they want something but deepdown they may want something else completely. This doesn’t happen intentionally, this is just how language works. It’s a bit fuzzy! Therefore, it’s a good idea to gauge the real need and respond accordingly, both at work and at home.

What I’m Reading

The man who is striving to solve a problem defined by existing knowledge and technique is not, however, just looking around. He knows what he wants to achieve, and he designs his instruments and directs his thoughts accordingly. Unanticipated novelty, the new discovery, can emerge only to the extent that his anticipations about nature and his instruments prove wrong. . . . There is no other effective way in which discoveries might be generated.

— Thomas S. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

Tiny Thought

Wise people do not whine about problems, they prevent them. Wisdom is prevention.

Before You Go…

Thanks so much for reading! Send me ideas, questions, reading recs. You can write to abhishek@coffeeandjunk.com, reply to this email, or use the comments. And… if you feel like I’ve done a great job writing this piece, be generous and buy me a few cups. ☕️

Until next Sunday,

Abhishek 👋