There’s Something Really Wrong With the Way We Learn Math

Or, mathematical thinking isn’t what you think it is

For the last few weeks, I’ve been itching to teach high school math to kids (and adults). The way I was taught in school—and the way it’s still taught in schools, and often on YouTube—hasn’t changed much, at least not in India.1

While channels like 3Blue1Brown and Veritasium do a fantastic job of making broader topics exciting, the same can’t be said for fundamental high school math concepts. When it comes to the nuts and bolts of maths, the fun just disappears. This might sound unpopular, but I’d call Khan Academy a slightly upgraded version of a textbook—it’s not the best, but definitely more engaging than the dry material in traditional math books.

Simply put, the way we teach high school math isn’t fun. On the other hand, when I pick up a book by Steven Strogatz, it’s a joy to read. Things come alive. Math feels fascinating.

WOULD IT FEEL NORMAL TO BE UNABLE TO READ?

In the past two hundred years or so, we made a fundamental decision: to teach everyone how to read and write. This decision is so foundational that it’s hard to imagine what our world would look like without it.

If you really wanted to mark a date when we first became human, you could pick the day when our ancestors decided to give language to everyone. Well before organised religion or codified laws, we chose to follow this implicit rule: Thou shalt teach thy children language.

The radical project of global literacy has been a huge success. Illiteracy hasn’t disappeared, of course, but it’s become much more rare.

At the same time the great campaign of global literacy was being undertaken, another radical decision was made: teach everyone the basics of math. Today, in elementary and high schools around the world, more than a billion children study math.

And it’s a disaster.

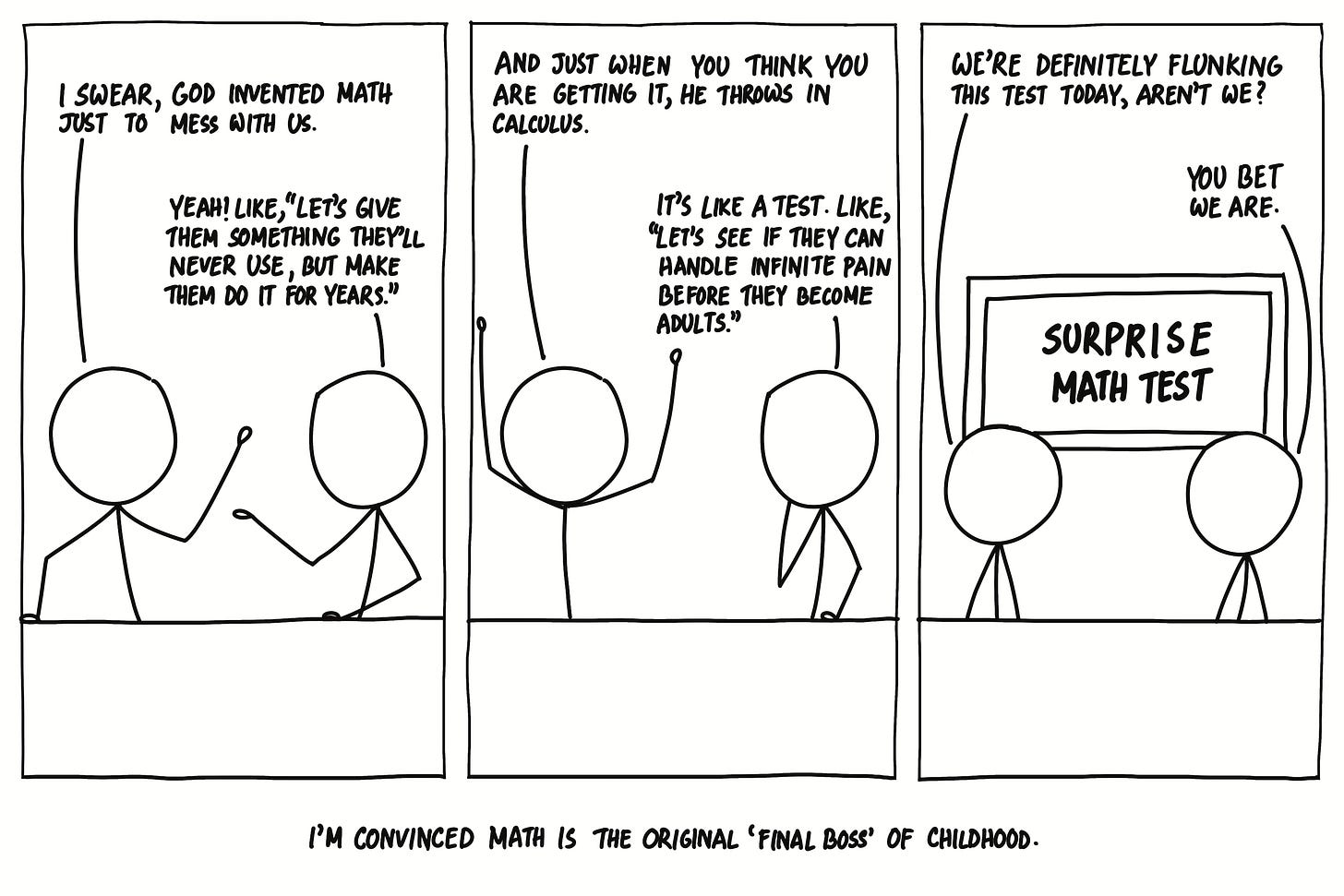

Hundreds of millions of children suffer in silence. They feel like they don’t understand anything, and flip-flop between utter detachment (they see absolutely nothing useful in studying math) and the humiliating sensation of simply not being smart enough.

If you ask kids what’s the most difficult subject, math ranks at the top of the list. It’s also, by far, the most hated. Hate is a very strong word. But if you ask what’s their favourite subject (not the same kids, of course), math is usually again in first place (other than physics). For some students, it’s the most fun subject.

This is a strange phenomenon indeed. Why is it that struggling with math is often seen as normal? Imagine if the same attitude applied to reading—would it seem normal for a kid not to know how to read? Or to view people who can read fluently as strange or weird? It’s worth asking why math, unlike reading, is treated this way.

Solving high school math problems should be as easy as tying your shoelaces. If that’s not the case (spoiler alert: that isn’t the case), then I strongly believe there’s something really wrong with the way we’re teaching math.

WHY ARE KIDS GRABBING THE WRONG END OF THE SPOON?

To explain why some kids are good at math and others aren’t, two hypotheses are usually floated.

The first is that it’s simply a question of motivation. Kids aren’t good at math because they don’t like it, and they don’t like it because they don’t see how it’s useful in their day-to-day lives. I used to think the same for a long time.

But do kids really think that history, for example, is useful in their everyday lives? That doesn’t make it any less intelligible, and history classes don’t throw people into a state of panic. You’ve never seen kids start crying because they don’t understand what a war or a revolution is.

Kids who struggle with math know it’s useful—at least for doing well in school and getting into a good university. They might not fully grasp why math matters, but they’re aware that it does matter. I think the feeling of either not understanding or being excluded from something so important gives them plenty of reason to hate it.

The second hypothesis is just plain mean. It supposes that there’s a mysterious type of intelligence, mathematical intelligence, that’s unequally distributed amongst the population. This explanation is based on biology, postulating that there’s some kind of math gene. Those who are good at math are simply born that way, and the others are out of luck. Some people explain it in terms of left-brained and right-brained.

That this idea is so widespread is somewhat surprising in itself. There was a time when people believed that certain races were naturally made for working in the fields, while others were made for owning the plantation. More recently, it was said that women were incapable of flying fighter jets. All these ideas have been discredited, but they’re still so widely accepted.

Biological differences between people do exist, but they’re not as extreme as the examples above. It’s more like this: imagine a group of high school kids running a 100-meter race. Most students would finish. Some would take 11 seconds, others 13 or 18, and a few might need 30 seconds.

These differences come from more than just genetics—things like motivation, nutrition, lifestyle, and training also play a role. Genetics might explain a small part of the gap, but for a 100-meter race, it’s usually just a few seconds at most.

Now imagine a different race. Some students finish in 1 second, but a week later, over half the class still hasn’t crossed the finish line. That’s the kind of gap you see in math skills by the end of high school.

If you go back to the starting line, you’d find some students sitting there, frustrated. They’ll tell you math is the worst thing ever, useless in daily life, and that the teacher is a cruel one.

Would you really think genetics is the reason for this?

I want to convince you that the only reason some kids struggle with math is that no one has taken the time to give them clear instructions. No one has explained that math is a physical activity. No one has told them that math isn’t about things to learn—it’s about things to do.

Kids are grabbing the wrong end of the spoon because no one has ever told them that there was a right end to it.

Kids often don’t understand that the math teacher’s words aren’t meant to be memorised. They serve as guidance—clues and instructions to help them perform the real work quietly within their own minds. The real learning happens through the unseen mental effort a kid makes.

That’s why studying math the same way you study history or biology doesn’t work. It’s like taking detailed notes in a yoga class but never practicing the breathing exercises. Without actively working through problems, the effort is meaningless.