In Defence of Being Slow-Witted

Or, if Richard Feynman can afford to be a slow learner, so can you

👋 Hey there! My name is Abhishek. Welcome to a new edition of The Sunday Wisdom! This is the best way to learn new things with the least amount of effort.

It’s a collection of weekly explorations and inquiries into many curiosities, such as business, human nature, society, and life’s big questions. My primary goal is to give you some new perspective to think about things.

A request: If you like this essay, could you do me a favour and hit that 🤍 heart so that it becomes a ♥️ heart? This helps me understand what kind of topics I should write more about. This also signals Substack that more people should read this essay.

One more thing: I’m trying to make a more conscious effort to personally know all of you. If you are interested in chatting over a video call, my calendar is open. Looking forward!

Q: Is our obsession with cognitive speed a valid measure of intelligence?

Our society extols the virtue of speed way too much. Metaphors like “quick-witted,” “nimble,” and “a fast learner” are frequently used to praise cognitive abilities. Even our evaluation criteria favour those who can process information swiftly, solve problems in record time, and make snap decisions.

But I’m not convinced that “mental speed” is a genuine reflection of intelligence.

You see, according to this perspective, a person’s cognitive advantage or disadvantage can be attributed to their processing speed. This suggests that the human mind operates much like a computer, where the number of operations per second determines performance in cognitive tasks.

But this perspective is flawed because the human brain is a far cry from a mere CPU, and the act of thinking is more nuanced than the clockwork precision of a particular set of operations per second.

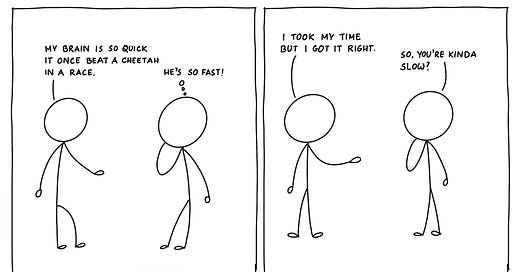

Another critical flaw in this obsession with mental speed lies in the assumption that it’s a monolithic concept. In reality, mental speed encompasses various processes, such as attention, perception, analysis, decision-making, and execution. Each of these processes can be fast or slow independently of the others. For example, someone with great sense of logic can be slow in creative or lateral thinking. This is why a chessmaster is not automatically a good strategist.

In addition, there’s no evidence that suggests a strong correlation between different aspects of mental speed. Being a quick learner, for example, doesn’t necessarily translate to faster analytical thinking.

While standard tests (such as IQ tests) are excellent tools for assessing performance in a controlled and kind environment, they may not provide a holistic view of an individual’s intellectual capacity in a wicked world.

Moreover, there’s evidence to suggest that general intelligence is better expressed by challenges unrelated to speed.

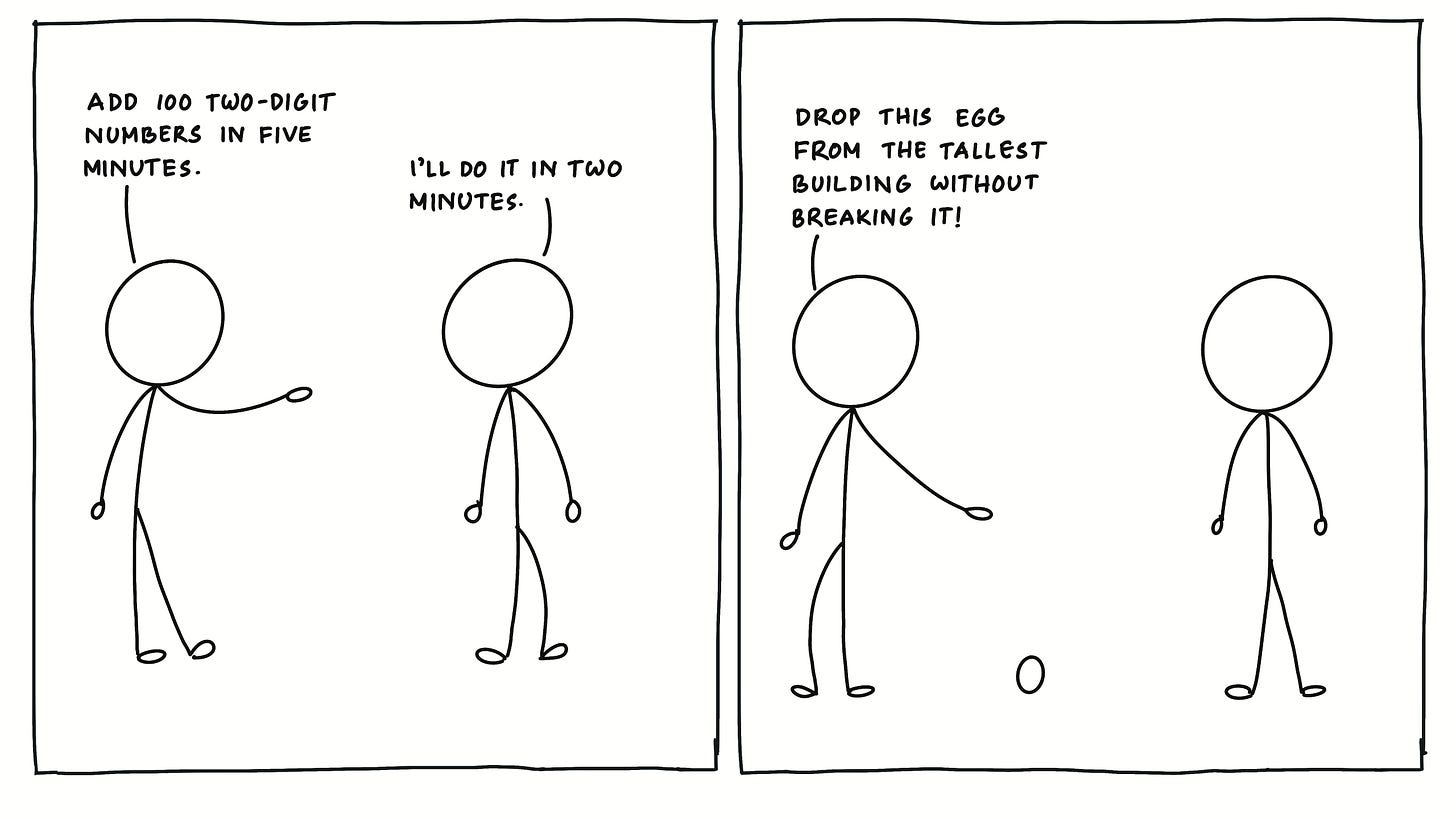

Imagine the following scenarios:

The first scenario assesses rapid mental arithmetic, while the second challenges creativity, innovation, and problem-solving. If we prioritise speed, we may overlook the intricate web of skills that contribute to true intelligence.

Speed is definitely a good indicator of intelligence. But it’s neither the main nor the only indicator. Having it is good, but not having it doesn’t mean you are stupid.

The super popular and beloved Japanese television series called Old Enough is a reality show where remarkably young children of age 2–5 carry out daily errands (such as getting groceries, to dropping off dry cleaning) for their parents. The children perform these mundane tasks with a persistence and resourcefulness that can astonish even the most seasoned adults.

Regardless of whether you think the show is scripted, it offers something profoundly intriguing — the two essential yet rare resources to hone one’s problem-solving skills: autonomy and time.

You see, unlike real life, where we often rush to find or provide solutions, the show allows these pint-sized prodigies the space to unravel challenges on their own. It’s a stark difference from our contemporary world which rarely offers individuals, especially children, the time to let their minds wander and experiment freely.

And this fixation on speed extends beyond tests and trials; it permeates our educational systems and work culture too. For example, in classrooms, we often reward the students who raise their hands quickest. We gravitate toward those who promptly provide answers in meetings, even if they lack depth or nuance.

This emphasis has led to an oversimplification of intelligence. We’ve reduced the intricate tapestry of “genius” to being a “fast learner” or a “quick thinker,” while overlooking essential qualities such as insight and perceptiveness. These are the qualities that allow individuals to see beyond the surface, to connect dots that others might miss, and to question the status quo.

Speed indeed matters, especially in time-sensitive situations. But when we elevate speed to the core of our understanding of intelligence, we risk missing out on the deeper dimensions of human intellectual capacity.

Being slow doesn’t equal to being dumb. It just means you approach problems slightly differently than others. To give a personal example, I’m a very very slow learner. I generally take a lot more time than others to pick up on new things.

I have to gather information, mull over them, cultivate a mental model in my mind, and then, and only then do I start to pick up speed. Does that make me dumb? I don’t think so. Does that make me slow? Yes, but only if you are judging by how fast I pick up on new things. Is it bad? I don’t think so. It’s just how I function.

I accelerate slowly, but once I pick up momentum, I’m as good as others, if not better. I’ve also often noticed that my understanding of a subject becomes deeper and broader than others. This is clearly an advantage. Knowing this prevents me from putting undue pressure upon myself to become a fast learner.

Intelligence is a complex symphony, and to truly appreciate it, we must listen carefully to all its notes, not just the quick ones.

But in any case, if you’re still not convinced about the unimportance of mental speed, I’ll have to bring in a big gun to make my case stronger.

Enter Richard Feynman.

Feynman spent a considerable amount of time in Japan in the 1950s. Everywhere he went, whoever was working in physics would tell him what they were doing and he’d discuss it with them. They would tell him the general problem they were working on, and would begin to write a bunch of equations.

“Wait a minute,” Feynman would interject. “Is there a particular example of this general problem?”

“Why yes; of course.”

“Good. Give me one example.”

As Feynman narrates in Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman:

That was for me: I can’t understand anything in general unless I’m carrying along in my mind a specific example and watching it go. Some people think in the beginning that I’m kind of slow and I don’t understand the problem, because I ask a lot of these “dumb” questions: “Is a cathode plus or minus? Is an an-ion this way, or that way?”

But later, when the guy’s in the middle of a bunch of equations, he’ll say something and I’ll say, “Wait a minute! There’s an error! That can’t be right!”

The guy looks at his equations, and sure enough, after a while, he finds the mistake and wonders, “How the hell did this guy, who hardly understood at the beginning, find that mistake in the mess of all these equations?”

He thinks I’m following the steps mathematically, but that’s not what I’m doing. I have the specific, physical example of what he’s trying to analyse, and I know from instinct and experience the properties of the thing. So when the equation says it should behave so-and-so, and I know that’s the wrong way around, I jump up and say, “Wait! There’s a mistake!”

Before You Go…

If you’re finding this newsletter valuable, share it with a friend. Also, consider subscribing. If you aren’t ready to become a paid subscriber yet, you can also give a tip by buying me a coffee. ☕️

I’ll see you next Sunday,

Abhishek 👋

PS: All typos are intentional and I take no responsibility whatsoever! 😬