👋 Hey there! My name is Abhishek. Welcome to a new edition of The Sunday Wisdom! This is the best way to learn new things with the least amount of effort.

It’s a collection of weekly explorations and inquiries into many curiosities, such as business, human nature, society, and life’s big questions.

The latest two editions are always free, the rest are available to paid subscribers.

If you like this essay, could you do me a favour and hit that 🤍 heart so that it becomes a ♥️ heart? This helps me understand what kind of topics I should write more about. This also signals Substack that more people should read this essay.

Q: Does meritocracy really deserve so much limelight?

There’s a lot of chatter about meritocracy these days.

Some claim meritocracy is a myth. Some claim, even if it’s not a myth, meritocracy is bad for the society. Then there’s another school of thought which suggests that it doesn’t matter if it’s a myth or not, but a belief in meritocracy is bad for everyone. Meritocracy makes everyone miserable. Meritocracy harms even the winners.

When you assess any particular practice or idea or philosophy in isolation, it’s pretty easy to glorify or vilify it, but this may not necessarily reflect reality.

In reality, there are various other factors that rub off each other and affect the overall outcome significantly. As I’ve mentioned multiple times (and I’ll continue to mention until my voice turns hoarse), truth is never black and white, especially subjective truth. Complex systems should be evaluated as an ecosystem. A complex system (such as a society) isn’t made up of a chain of causal links. And the question really isn’t about meritocracy.

Therefore, instead of taking on meritocracy head on, let’s talk about other related societal practices. Let’s start off with something that people aren’t a big fan of: nepotism.

Nepotism exists in every egalitarian society. If you have the means and power, you would definitely give your friend or loved one a leg up. It’s the most natural thing to do. You’d rarely hear a conversation that goes like this:

The problem happens when we push it too far and let someone reap the benefits despite having no merit. (Think low-stake government jobs where there’s no assessment of merit.)

But there are domains where it’s hard to hide the results. Take showbiz for example — such as standup comedy and the movie business. If you know who’s who, all you’ll get is a foot in the door. After that, you are on your own.

After completing Seinfeld, Jerry Seinfeld had to start from the bottom and reinvent himself in the comedy scene after a near ten-year hiatus.

On the other hand, Uday Chopra, the son of the famous Indian film director Yash Chopra and the younger brother of Aditya Chopra, (who is also a prominent filmmaker) never made it big in the Hindi film industry despite having all the opportunities in the world.

While it can be argued that Jerry Seinfeld (or anybody for that matter) became successful because of merit, there just might be another equally important factor that we haven’t considered yet: luck.

What fascinates me the most is that no matter how much we agree with its existence, we never give “luck” enough credit for our success. I mean, it just doesn’t feel right to let someone else take the credit for all of the hard work we did, right? (Although we never shy away from blaming “bad luck” for our failures.)

We undervalue and underappreciate luck only because, unlike hard work, it cannot be easily measured.

Keith Gill became extremely rich during the GameStop stock trading saga. Gill’s online posts and videos about investing in GameStop gained a lot of followers on social media. This skyrocketed the stock price in January 2021, leading to huge losses for some hedge funds and making many regular investors super rich.

You can also say that he got lucky. He had merit, yes, but he was also at the right place and the right time — luck! That might be true, but the age old adage, “Fortune favours the brave” (or in this case, “the prepared”) doesn’t exist without reason.

In a fair world, hard work should increase your odds of being at the right place at the right time. This brings me to yet another piece of the puzzle: fairness.

Now, fairness is trickier than luck because, unlike luck — which all people usually agree upon — fairness is not easily agreed upon, especially by opposite parties.

In 2012, Greece was in its fifth year of recession and reliant on aid from the EU. Germany, the largest contributor in Greece’s bailout, thought it was unfair to support Greece as it lived beyond its means and piled up debts it couldn’t repay.

The Greeks, on the other hand, were certain that it was unfair for them to suffer years of slim budget and high unemployment (under austerity measures) in order to repay richer neighbouring countries (such as Germany).

The grievances weren’t unreasonable on either side. But too much focus on what’s the right thing to do (i.e., fairness) took away focus from what’s the most effective thing to do. Often they aren’t the same.

This finally brings me to the fillet of this inquiry: meritocracy.

Meritocracy implies fairness in assessment and opportunity. It effectively says: If we have an unbiased system and everyone gets equal opportunity, we’ll are good.

On paper, this sounds logical because it implies we are the masters of our own fate. But it doesn’t take two major factors into consideration: human nature and luck.

If you believe a system is completely fair, then you are responsible for your success, yes, but also for your failure. Meaning, if you are underprivileged, or poor, or in need of help, that’s totally on you. You are completely on your own.

Also, I’ll beat you to the ground and climb up the social ladder by stepping on you without batting an eye — and it’ll still be fair. That’s basically a dog-eat-dog world — kind of like Squid Game. Fair, yes, but also brutal.

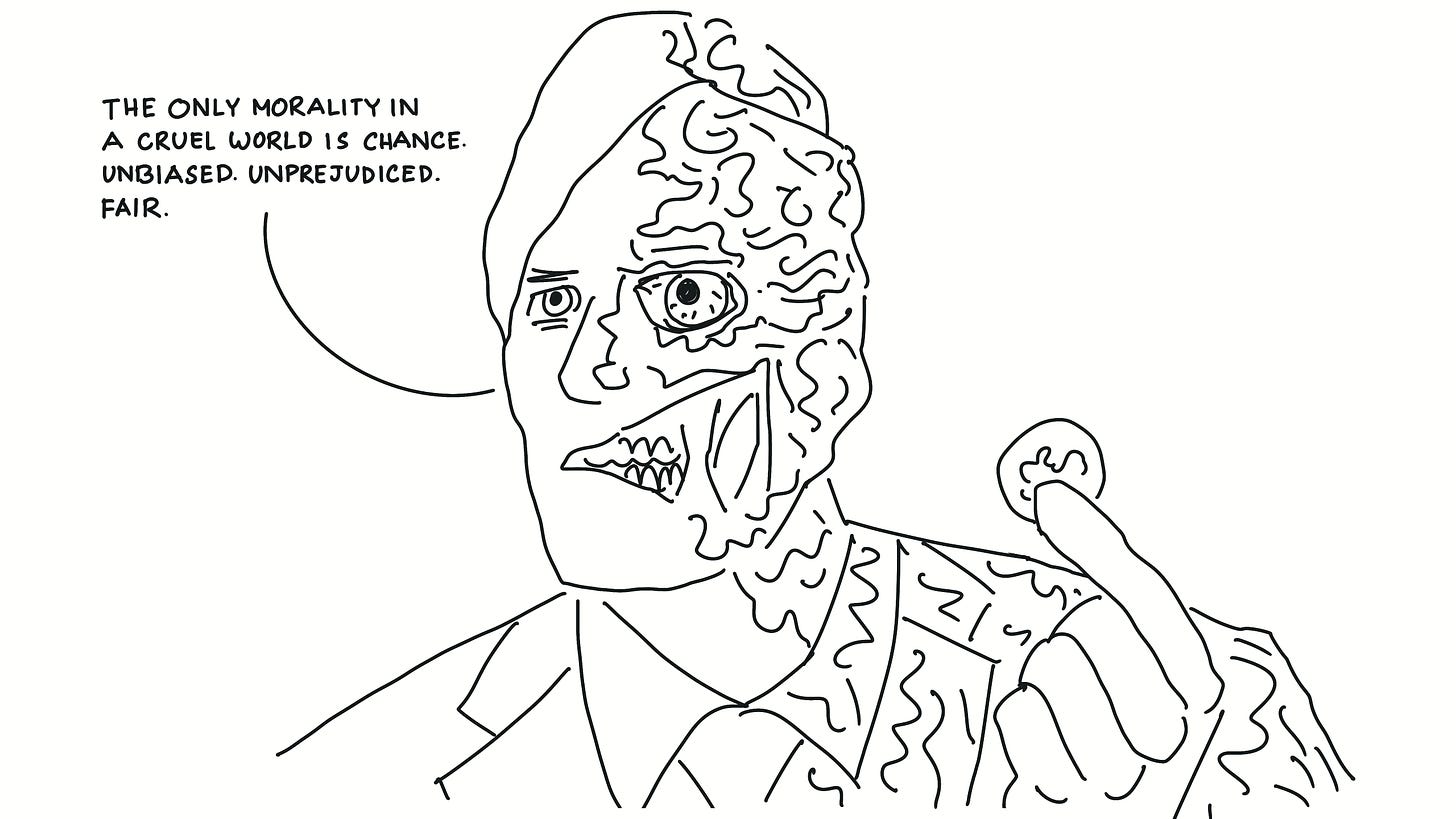

Fairness goes both ways in the spectrum. If “Squid Game” is one extreme, the other extreme is a “Coin Toss” — where everything is decided by chance. Think Harvey Dent/Two-Face calling all the shots and deciding who wins or loses based on a coin toss.

Now, this one may sound logical on paper, but it doesn’t “feel” right because it gives way too much importance to chance. We aren’t in control. Our efforts don’t matter. So, instead of striving towards greatness, we’ll descend into nihilism in this world.

I dunno about you, but I don’t want to live in either of these worlds.

The safe zone is somewhere in the middle.

A good system is one that has fair rules and “strives” to give equal opportunity to all, but also where individuals appreciate the value of chance and don’t expect the system to be 100% perfect and take care of each and every small thing.

A good system basically does three things really well:

First: A good system supports the less fortunate (for e.g., welfare programmes) and makes an effort to lift them up (for e.g., free education) so as to level the playing field for all.

Most successful governments invest heavily in welfare programmes. This gives a strong signal that you are not on your own. Today you might be doing okay, but if you tomorrow things go south, the system will have your back.

Second: A good system provides tremendous upside to change makers and risk takers (for e.g., you can start a business from your bedroom) so that people always strive to do better and push things forward.

This is where a belief in meritocracy really shines. If you have the brains and the cojones to make smart bets, and if the system encourages this, you’d focus a lot lot more on innovation. That’s why, even though 9 out of 10 fail, people still start startups — simply because the upside is so high. Silicon Valley is a great outcome of this.

Third: A good system doesn’t let any single entity have too much influence (even via merit). The President or the Prime Minister of a country may enjoy the “most” amount of power, but a stable system always puts guardrails so that they can never have “too much” power to disrupt the whole system itself. Otherwise, it results in Nazi Germany or modern day China and Russia — not the most ideal government systems in my opinion.

Thus, the question isn’t really about meritocracy. The question is about maintaining a balance in the ecosystem — between fairness and effectiveness, effort and luck, upside and downside, nepotism and meritocracy — so that there’s little overall downside when thing go wrong but tremendous overall upside when things go right.

A system can never be problem-free; it can only be problem-proof.

Before You Go…

If you’re finding this newsletter valuable, share it with a friend. Also, consider subscribing. If you aren’t ready to become a paid subscriber yet, you can also give a tip by buying me a coffee. ☕️

I’ll see you next Sunday,

Abhishek 👋

PS: All typos are intentional and I take no responsibility whatsoever! 😬